Bobby Tulloch and the Snowy Owls of Fetlar

There was a moment, from 1967 to 1975, when the Shetland island of Fetlar was briefly thrust into the national spotlight. The reason for this great excitement was the discovery, by naturalist Bobby Tulloch, of Britain’s first breeding Snowy Owls (Nyctea scandiaca).

These large, beautiful birds are white with dark speckles, have great yellow piercing eyes, and comically fluffy feet. These days, Snowy Owls are recognisable to most as Harry Potter’s pet ‘Hedwig’.

These large, beautiful birds are white with dark speckles, have great yellow piercing eyes, and comically fluffy feet. These days, Snowy Owls are recognisable to most as Harry Potter’s pet ‘Hedwig’. Their wingspan can measure up to five feet across!

Snowy Owls normally live on open grasslands in Canada, Siberia and northern Scandinavia. They roost on the ground, on windswept rises in the landscape, and hunt lemmings and other small creatures. Occasionally, when food is in short supply, Snowy Owls venture out of their usual territory.

Bobby Tulloch becomes the first Shetland representative of the RSPB

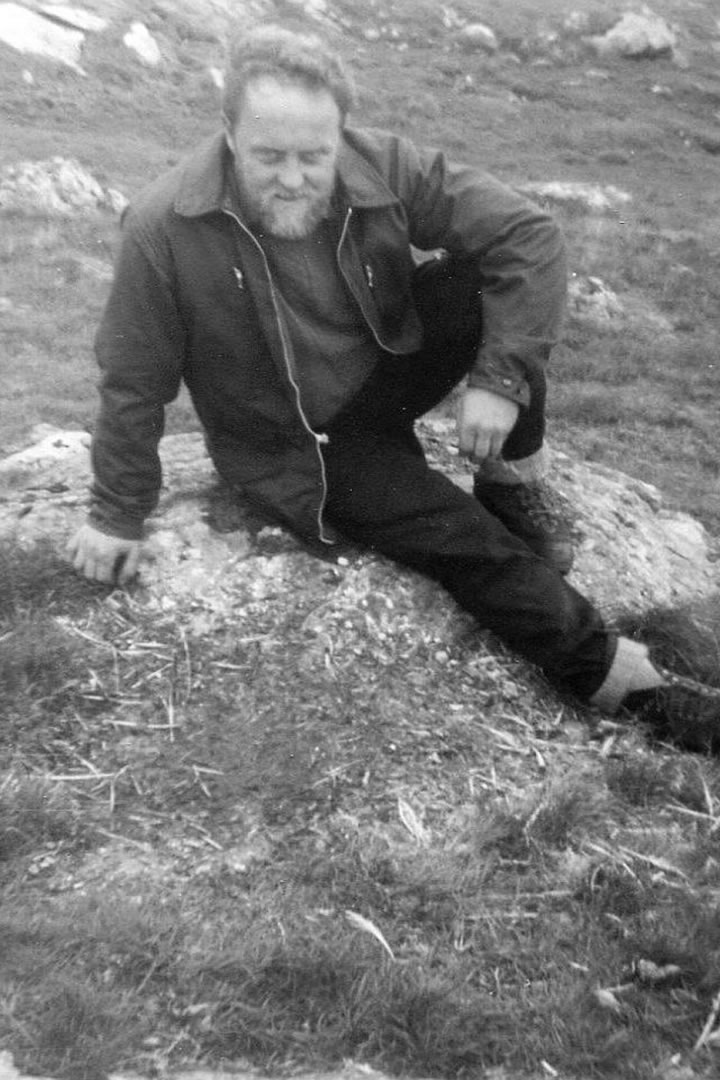

Bobby Tulloch, known as Tucker to his friends, was a self-taught naturalist from the island of Yell. Born in 1929, he spent much of his young life outdoors. His interest in natural history began at a young age, and this was encouraged by his primary school teacher, who gave him the British Bird Book. Bobby said that; “the study and enjoyment of our abundance of wild creatures easily compensated for the lack of material pleasures of a wartime childhood.”

To spot birds, Bobby was entrusted with German binoculars (a souvenir from his grandfather’s time in Germany as a prisoner of war). After leaving school, Bobby worked as a baker, before being offered the post of the Shetland representative of the RSPB in 1963.

This post was ideal for him, and he was a warm and welcoming ambassador for Shetland. Bobby was an excellent wildlife photographer and tour guide, often ferrying visitors through wild seas in his small haddock fishing boat, Consort. The boat was known to be temperamental, so Bobby was also a proficient mechanic!

His other skills included being a keen fisherman, and accomplished musician who taught himself how to play the fiddle and wrote hilarious songs which were performed at concerts. Bobby could also easily identify birds without binoculars.

Snowy Owls were beginning to be seen from time to time in Shetland. In 1963, Bobby and photographer Dennis Coutts attempted to get close to one in Whalsay by dressing up in a moth-eaten pantomime horse costume!

An amazing discovery

In 1967, whilst Bobby was guiding Swiss birdwatchers around Fetlar, one of his party noticed Snowy Owls sitting on a desolate slope at Stackaberg.

Snowy Owls normally look bored, however Bobby noticed that the male was acting very aggressively.

He took a moment away from his party to “look for owl pellets” and found a nest with 3 eggs. Aware that announcing his discovery could endanger the owls and their nest, he kept this information quiet and at the first available opportunity, called the RSPB.

A reserve was quickly set up around the nesting area and an around-the-clock watch was kept on the Snowy Owls. An observation hide (which a neighbour had intended to be his garden shed) was erected about 100m from the nest, and an empty house was secured on Fetlar for the volunteer wardens.

That first year, 7 eggs were laid, six young were hatched, and five owls were reared. There was great interest in the Snowy Owls, but Bobby handled journalists from the daily papers with ease, graciously taking them to view the birds, and even travelling to London for a television interview.

Bobby also took the influx of ornithologists who wanted to see the Snowy Owls on his boat to Fetlar. For those not fit enough for the hike to Stackaberg, he would sail Consort near to the nest, where the birds could be observed from the outer deck with binoculars.

The Snowy Owls bred on Fetlar for eight years, successfully raising 23 young owls.

About the Snowy Owls of Fetlar

In the Arctic, Snowy Owls usually eat lemmings, but on Fetlar, the very large population of rabbits was the main food source. It may have been the large quantity of food that attracted the Snowy Owls to the island. Unfortunately, during the Snowy Owl’s time on Fetlar, the rabbit population was exposed to myxomatosis – a lethal virus to rabbits.

By 1971, rabbits had almost vanished from the island, and the Snowy Owls began to eat waders instead, including Oystercatcher, Curlew, Whimbrel and chicks of Common Gulls, Great Black-backed Gulls and Arctic Skuas.

Slowly, the rabbit population recovered, and by 1975 had returned to pre-epidemic numbers. During the years that rabbits were scarce, the Snowy Owls laid fewer eggs and reared fewer young.

Most hunting occurred when the light was dim, between 21:00 and 03:00. The male Snowy Owl would provide food for the female and her chicks. He was not permitted to feed the chicks though. The food was torn up and fed to the chicks by the female, who ate bits herself at the same time.

9 days after hatching, the owl chicks’ eyes were fully open. After 16 days, the owlets began to wander about 1m from the nest, but would always return to be fed. After 45 days, the young owls would attempt their first flight. A couple of weeks later, they would be fully independent.

Owl marital problems

One winter’s day, Bobby found the male Snowy Owl had collapsed from exhaustion. Secretly, he took the bird back home to Mid Yell. There he perched the Snowy Owl on his wardrobe, fed him scraps of meat, and nursed him back to health! Soon enough, the male owl was well enough to return to the wild, and successfully bred for another six years.

However, this was not always with the same female! Though the same pair of owls nested from 1967 to 1974, in 1973 and 1974 the male found an additional lady friend. During those years, two females laid eggs at two separate nests. However, the male only supplied the first female with food and did not provide for his new love’s nest.

The following year, 1975, the second female moved to the main nest and the pair reared four chicks.

In the winter of 1975/76 the male disappeared, and breeding stopped. Unfortunately, the older male had chased off his young male offspring, so in 1976, there were Snowy Owl females on the island, but no new males arrived. One or two females continued to return every year until 1993.

Though Snowy Owls can still be seen occasionally, none have bred in Shetland since.

After the Snowy Owls of Fetlar

Bobby Tulloch continued as the RSPB representative in Shetland until 1985, and wrote the magnificent book, Bobby Tulloch’s Shetland. He continued to give tours and talks and published annual reports of bird sightings. He never stopped caring deeply for wildlife in Shetland.

He passed away in 1996, two years after receiving an MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List.

The lovely island of Fetlar is still a must-visit for ornithologists, who visit to see rare Red-Necked Phalarope that seem to love gathering at the Loch of Funzie. Red-throated divers can be spotted, and the island has a great number of snipe also.

On the lonely hill at Stackaberg these days you will find a plaque dedicated to Bobby Tulloch, which starts “A friend remembered.” There is probably no better way to describe this amazing self-taught naturalist, who discovered the first Snowy owls to nest in Britain.

With grateful thanks to The Old Haa Museum in Burravoe, Yell for the photos used in this article, which were kindly donated by Bobby Tulloch’s surviving family.

For further reading please visit www.bobbytulloch.com and seek out Bobby Tulloch’s Shetland by Bobby Tulloch, Bobby the Birdman edited by Jonathan Wills & Mike McDonnell and Snowy Owls on Fetlar by Martin Robinson and C. Dustin Becker (British Birds Volume 79 Issue 5, May 1986).

An audiobook of Bobby Tulloch’s Shetland: An Islander, His Islands and Their Wildlife, narrated by his niece Caroline Keith, has been published by Yell based writer and naturalist Adrian Brockless. The audiobook also contains arrangements of two tunes written by Tulloch, arranged by Brockless and performed by the Nova String Quartet. All proceeds go towards the community of Yell.

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!