The story of Rackwick

I’m pretty sure that I’m not alone in thinking that Rackwick is my favourite place in the world.

Though it is only a few miles from Stromness as the crow flies, Rackwick always puts an edge on the appetite. We had a marvellous late supper of curried beef and eggs, and home-brewed ale. And oh, the peace of lying in a box bed, with the boom of the sea in your ears!

George Mackay Brown

It’s a beautiful valley on the island of Hoy, located six miles from the foot passenger ferry that lands on the island at Moaness.

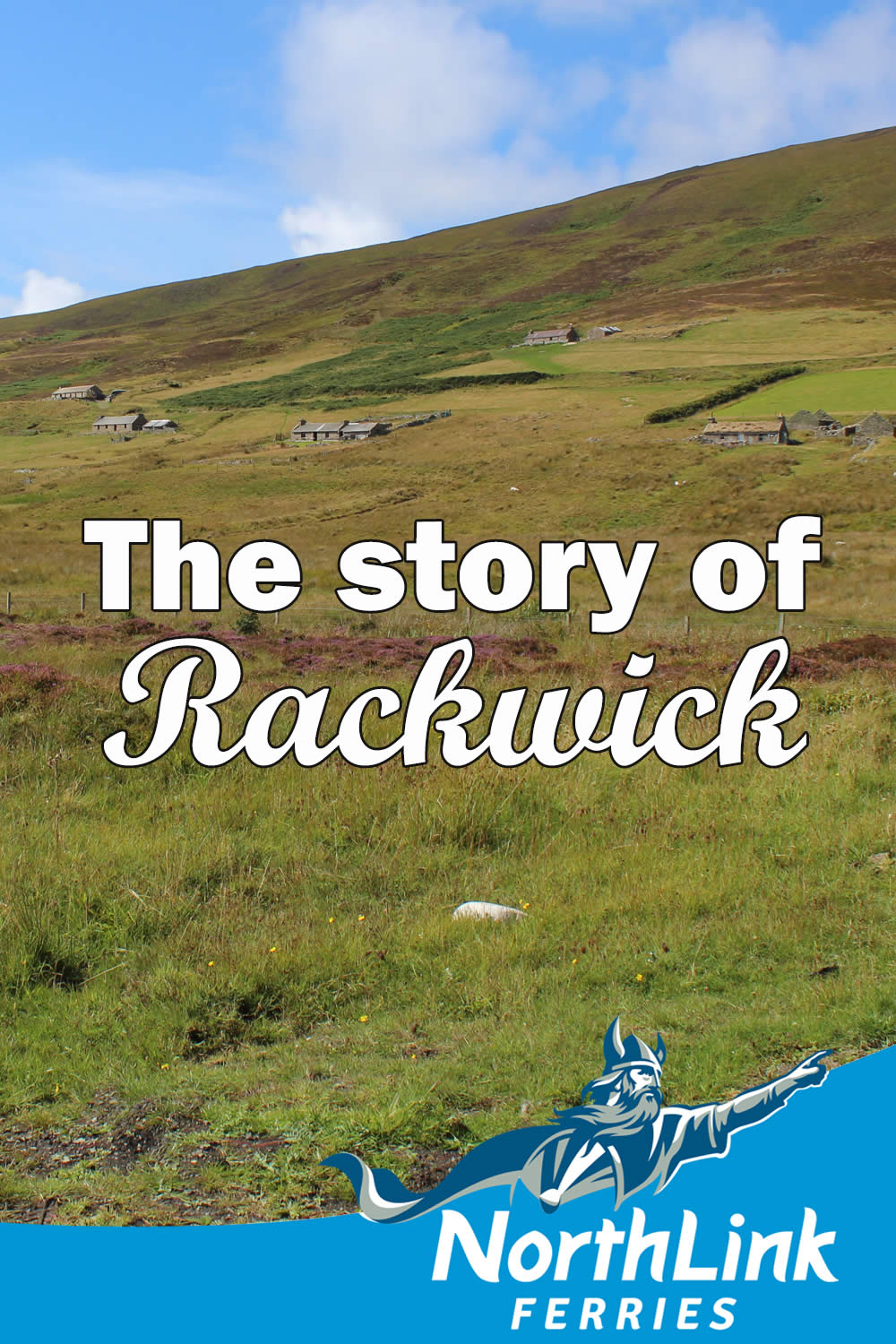

After a long walk through a dark heather pass between hills, a traveller will find themselves emerging out to a bright curving bay. Rackwick, from the Old Norse ‘Reka vik’ meaning ‘jetsam bay’, is surrounded by three hills. Two slopes stand at either side of a beach. Mel Fea is more a cliff than a hill, and Moor Fea is a green hillside littered with crofts. Behind Rackwick beach is Orkney’s tallest, Ward Hill. On a sunny day, this enclosed valley can become one of the hottest places in Orkney.

Rackwick beach is quite striking, with giant sea-smoothed boulders and a wide curve of pink sand. The amount of sand varies depending on winter storms. A burn, fed by the surrounding hills, flows lazily through the valley, and rushes out to sea over the pebbles – this must be crossed with care.

Rackwick is a peaceful place, perfect for gathering one’s thoughts. Only the sound of the sea can be heard on a summer day.

The first inhabitants

Though the Old Norse names of the surrounding hills indicate that Rackwick was known to islanders beforehand, the first known inhabitants of Rackwick were Covenanters. These were religious prisoners on board a ship which sank in 1679 off Deerness. 200 Covenanters were lost but 47 escaped. Though most were rounded up, some hid in Orkney. Of these, three men, Thomson, Ritch, and Willison ended up in Rackwick.

The first crofts to be built were Crowsnest, which was occupied by the Thomsons and had a circular kiln for drying oats and Scar, which was occupied by the Ritches. The building stone came from the fields or from the beach.

During the 18th and 19th century the community grew to over 100 inhabitants. More crofts were built: Blackdyke, Bunnertoon, Burnmouth, Greenhill, Groups, Midhouse, Moss, Mucklehouse, Outerhouse, Quernstones, Quholme, Rumin, Lower Rummin, Sandybraes, Shore, The Glen, The Mount, The Park and Windbreck.

Fishermen with ploughs

The inhabitants of Rackwick were crofters and fishermen. They had small crofts with a few acres of land, a milking cow and a handful of sheep. Often there was also a small walled plot where young crops sheltered before being transplanted into the field. The women and children looked after the animals and the men were skilled fishermen who set off into the wash of the bay.

The men shared their boats and had a winch to haul their vessels back ashore. When they returned the women would help them unload the catch and share it amongst the families. Widows and the needy folk of the valley were always given a share of the catch. The rest was dried for trade or for winter.

The men knew the coast intimately. They caught lobsters and cod. They scaled the cliffs for eggs, using simmans ropes made of heather. They took their boats to tricky spots to access such as ‘The Larder’ close to the Old Man of Hoy and came home with a silver bounty. Some men would even climb down to the base of the Old Man to a creek known as ‘The Trough’ and there they would fish all day for bream and cod. Then they would climb, carrying their heavy load in a basket, back up the cliff and home.

Life in Rackwick

Despite a life of toil, the folk of Rackwick were content and even quite prosperous. Peat-cured fish from Rackwick was sold all over the north of Scotland. Once caught, the fish would be split, cleaned, dried, and then hung in rows around croft chimneys (and chimneys in Rackwick were wide for this purpose). After some time, the fish would be hard and dry, ready to sell.

There was always great excitement in the valley whenever shop boats arrived in the bay. The Gleaner and the Endeavour came from Kirkwall and served all the isles. A shop boat would send a motorboat or dingy to pick up customers. Once on board the shop boats, the folk of Rackwick could buy groceries, draperies, meal, china, and paraffin. When good roads were built in the isles, floating shops were no longer necessary.

Every Sunday the folk of Rackwick would walk four miles to the Hoy Kirk along a dirt track. Later, the new school was used for church services and weddings. There was a great sense of community spirit and generosity in Rackwick. The crofters cut peats together and shared these. Most of the fields were fenceless. If a crofter were feeling poorly, others would always help with the work. Each croft had an open door for visitors. A visitor who knocked would have been considered a snob!

The School

One of the oldest buildings in Rackwick is the old Rackwick school. It began life as a croft but became a school in 1718. Later it became a cobbler’s workshop and it now serves as a folk museum. The new Rackwick school was built in 1879 and stayed open until 1953.

It is said that the Rackwick school taught 35 sea captains. In payment for their lessons, children would bring in a peat a day.

The emptying of the valley

As with all small places, the influence of the modern world was enticing to young folk and they began to drift from the isles. Religion looked with favour upon those who would improve themselves, and it was considered better to be a shop keeper in Hamnavoe (Stromness) than to farm and fish in Rackwick. Young folk left the valley, and the old folk began to die off. Crofts fell empty.

The school closed in 1953 when two of the last pupils, the Mowat brothers, fell off a raft in Rackwick burn and drowned.

By 1973, only one farmer, Jack Rendall, was left in Rackwick.

At Burnmouth the door hangs from a broken hinge

And the fire is out.

The windows of Shore empty sockets

And the hearth coldness.

At Bunnertoon the small drains are chocked.

Thrushes nest in the chimney.

Stars shine through the roof beams of Scar.

No flame is needed

To warm ghosts and nettles and rats

An extract from Dead Fires by George Mackay Brown

The new occupants of Rackwick

New life stirred in Rackwick. Doctors, teachers, and artists from Stromness and elsewhere on Orkney’s mainland began to buy crofts as holiday houses. Poet George Mackay Brown took a keen interest in the valley, and composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies moved to Bunnertoon in 1979. Jack Rendall married and in 1980 his daughter Lucy was the first child to be born in Rackwick in 32 years.

At first many of these holiday houses were used as an escape from modern life. Many crofts had no electricity, and gas stoves and paraffin lamps were used. Old Orcadian box beds were slept in. These were almost like a wooden cupboard, enclosing the occupant inside to stop heat escaping. George Mackay Brown wrote:

“Though it is only a few miles from Stromness as the crow flies, Rackwick always puts an edge on the appetite. We had a marvellous late supper of curried beef and eggs, and home-brewed ale. And oh, the peace of lying in a box bed, with the boom of the sea in your ears!

But to wake up in a box bed with the sound of rain in the thatch and windows is not so pleasant. When Rackwick weeps, its grief is long and forlorn and utterly desolate.”

Rackwick today

Burnmouth bothy was bought and set up by the Hoy Trust as a bothy for campers. Electricity arrived in Rackwick in 1979. In 1960 all school pupils on the island of Hoy began to go to the school at North Walls so the Rackwick school became a youth hostel.

Most of the old crofts have been occupied and modernised, and new houses have appeared in Rackwick valley. Many now have electricity and modern comforts.

Every day in the summer a handful of visitors arrive in Rackwick. Some head to the beach, crossing Rackwick burn to the sand, to paddle in the waves. Some camp at Burnmouth. Midges can be a problem in Rackwick, but a driftwood fire or strong sea breeze will keep them at bay.

Other visitors climb the slope of Moor Fea to walk to the Old Man of Hoy. The best viewpoint for the Old Man is an hour’s walk to the cliff directly opposite. The bravest visitors will scale the 449ft high sea stack. Between 20 and 50 people every year climb the Old Man of Hoy.

Those on the path to the Old Man will get one of the best views of Rackwick bay, one of the most beautiful places in the Orkney islands.

Poem and prose reproduced by permission of the Estate of George Mackay Brown.

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!