The day we caught an Orkney Vole

There are many unique aspects to the Orkney islands – the pace of life, the amazing archaeology, the wild landscape and weather – but one is less well-known. Orkney has it’s own subspecies of vole!

Vole remains were found in the rubbish pits at the Neolithic village of Skara Brae. The early settlers in Orkney transported sheep, pigs, cattle and red deer in boats to Orkney, and voles must have arrived with them. Since then the Vole evolved into its own Orkney race which measures between 10-13 cm, weighs between 30-70g, and lives for two years.

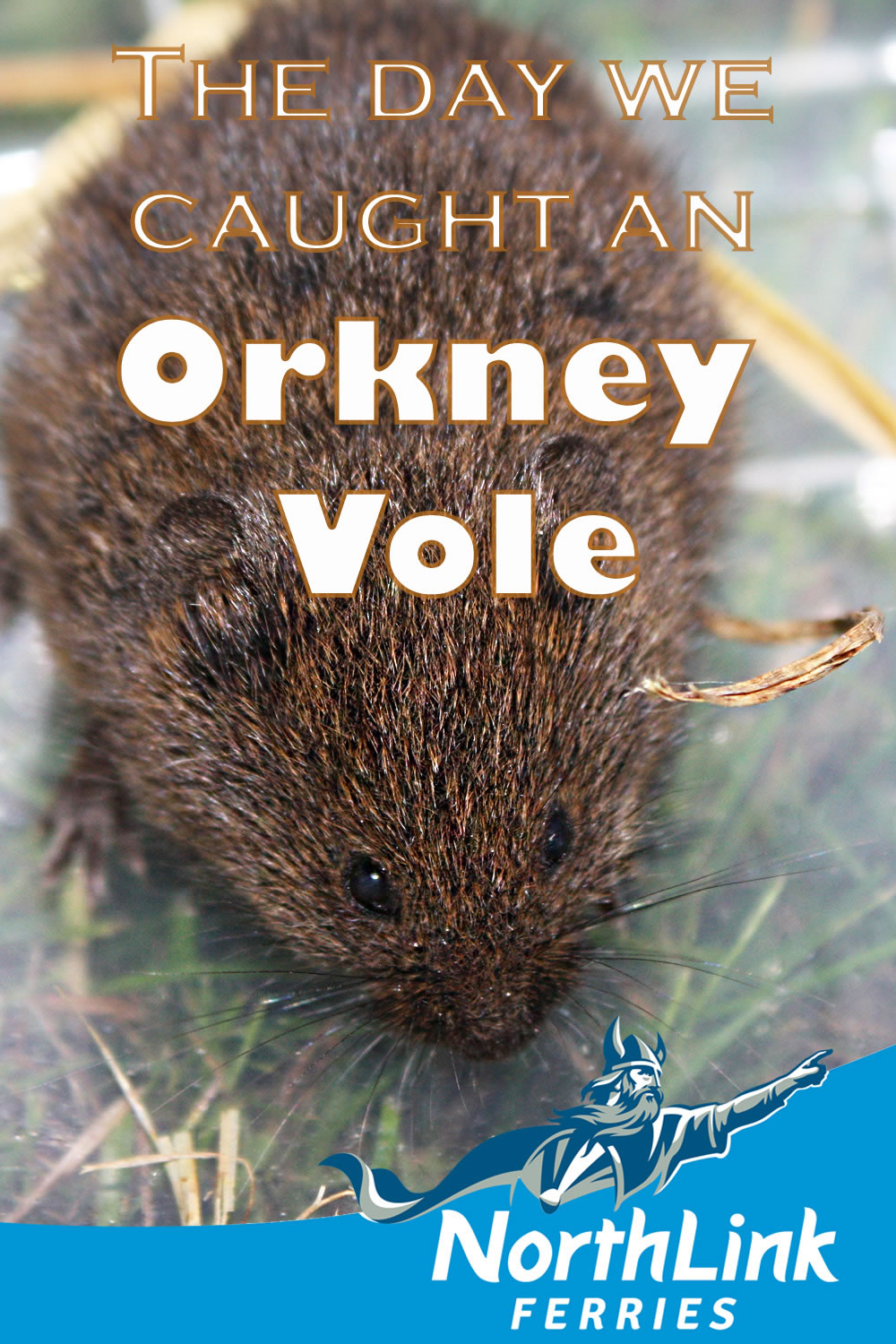

Orkney Voles are twice the size of field voles found on mainland Britain. They have a stocky body with a blunt, rounded snout and they feed on the leaves, stems and roots of plants. Unlike many other rodents they are active during both the day and night. They live in rough grassland adjacent to moorland, or in ditches running through agricultural land. Orkney Voles represent an important source of food for birds of prey such as hen harriers, kestrels and short-eared owls. The other main predator of voles is the domestic cat.

One of the reasons Orkney is attractive to birds of prey is that Orkney Voles represent an abundant, active-by-day food-source that is easily-caught. Or so I thought!

I thought it would be interesting to catch an Orkney Vole; to see one up close and take its photograph. To do this, I contacted Scottish Natural Heritage and asked their advice. They recommended that I use a Longworth trap – which is a humane trap with a tunnel that the creature must go through to reach a roomy compartment.

The Longworth trap has a tiny trip wire, which closes a metal door behind the animal. I was advised to only trap an Orkney Vole for study purposes, and to check the Longworth trap regularly. I was also told to keep it well-supplied with food. I filled the trap with hay so that anything I caught would be able to stay warm.

I placed the trap in an area of rough grassland in Stenness, 200m from my house, so that I could check the trap often – first thing in the morning, at teatime and at midnight. The area in which I placed the trap had plenty of evidence of voles in the form of vole tunnels – circles of eaten grass. As Orkney Voles eat the roots of grasses, diced carrots were used as bait. Having the same texture as roots, carrots would also provide a water source for a trapped animal.

I checked the Vole Trap every day, each day hoping to find the trap door closed and an Orkney Vole inside. Each day I went home disappointed. Something was eating the carrots in the trap, that was for sure. Something was even having a poo in the trap. But nothing was tripping the wire to close the trap door!

Orkney Voles have lived in the islands for a long time. Close studies have found a genetic match with voles in Belgium and Orkney Voles are thought to have originated from there 5,100 years ago. Vole remains were found in the rubbish pits at the Neolithic village of Skara Brae. The early settlers in Orkney transported sheep, pigs, cattle and red deer in boats to Orkney, and voles must have arrived with them. It is clear that there was a sophisticated maritime trade network along the Western Atlantic fringe in Neolithic times!

Since then the Vole evolved into its own Orkney race, known locally as a Cuttick, Voldro, Volo, or Cutto, which measures between 10-13 cm, weighs between 30-70g, and lives for two years. Interestingly voles from the islands of Sanday and Westray are lighter in colour.

My Orkney vole was proving to be elusive; the trap was still yielding no results. I had also put a carpet down on the rough grass near the trap – Orkney Voles often take shelter under pieces of carpet or corrigated iron – and I continued checking every day, but found nothing.

However, after nine days I finally caught a vole! Or rather someone in our family did. On ninth day of checking my Orkney Vole trap, my cat, Tilly, raced into my garden, carrying an Orkney Vole in her mouth as gently as a kitten – she wanted to play with it (and possibly chew it a bit when she was finished!) Cat and vole were seperated, much to Tilly’s annoyance! Luckily, the vole was unhurt.

I took the Orkney Vole’s photograph and watched him as he ate a piece of carrot. He was shaken at first, but then became quite active and explored his surroundings.

My daughter gave him a stroke and fell in love with him a little. All the time he seemed unfazed. I was left with the impression that Orkney Voles are remarkably resilient.

He was quite small, so I suspect he was a young vole – I was very pleased to offer him a second chance at life! After a short time I set him free in an area of rough grassland, far away from the cat! The Orkney Vole left with a squeak!

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!