Orkney men in the Nor’Wast

Orkney has had links to Canada and the Arctic, the Nor’Wast, since the 17th century. The islands were often the last port of call for explorers, traders, merchants, and whalers before they set sail across the Atlantic. In those days, uncharted areas of the world held as much excitement and mystery as space travel might have for us now.

Evidence of Hudson’s Bay Company ships in Orkney can be seen today in the Labradorite found on Stromness shores. This iridescent rock from Canada was used as ballast, dumped overboard when a ship’s hold was restocked with supplies.

Find out how the Nor’Wast left its mark on Stromness and Orkney.

1610 – Henry Hudson finds the bay

Much of northern Canada was unexplored in the 17th century. This immense area was covered in silver streams and lakes. In winter much of it was masked in ice.

Europeans were eager to explore the area to find the fabled Northwest Passage, a sea route from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the Arctic Ocean. Sir Henry Hudson was looking for the Northwest Passage on his ship Discovery when he found the bay – a massive bite into northeastern Canada measuring 470,000 square miles.

He continued his search in the Arctic for the Northwest Passage afterwards. However, navigating a ship through a vast desert of ice was a dangerous endeavour. After a winter locked in ice, the crew mutinied. They set Sir Henry Hudson and a few still-loyal men adrift in a small boat. They faded into a sea haar, never to be seen again.

1670 – The Hudson’s Bay Company is formed

In Europe, beaver fur was highly sought-after to make waterproof felt for hats, which had left the animal nearly extinct. In Canada there was a plentiful new source of beaver fur, available by trading with native people. For much of the 17th century the French had a monopoly on this supply.

The Hudson’s Bay Company was formed in London by Prince Rupert. It was granted a royal charter by his cousin, King Charles II to trade fur in all lands whose rivers drained into Hudson’s Bay. This area, later known as Rupert’s Land, covered much of North Dakota and Minnesota and 40% of what we call Canada today.

Hudson’s Bay Company ships sailed in early summer from London to the trading posts called forts on the shores of Hudson’s Bay. At the forts, First Nation and Inuit trappers would exchange beaver and fox furs for pots, blankets, and other European goods. The ships would return to Britain in November loaded with 80,000 to 100,000 furs.

1688 – Europe goes to war

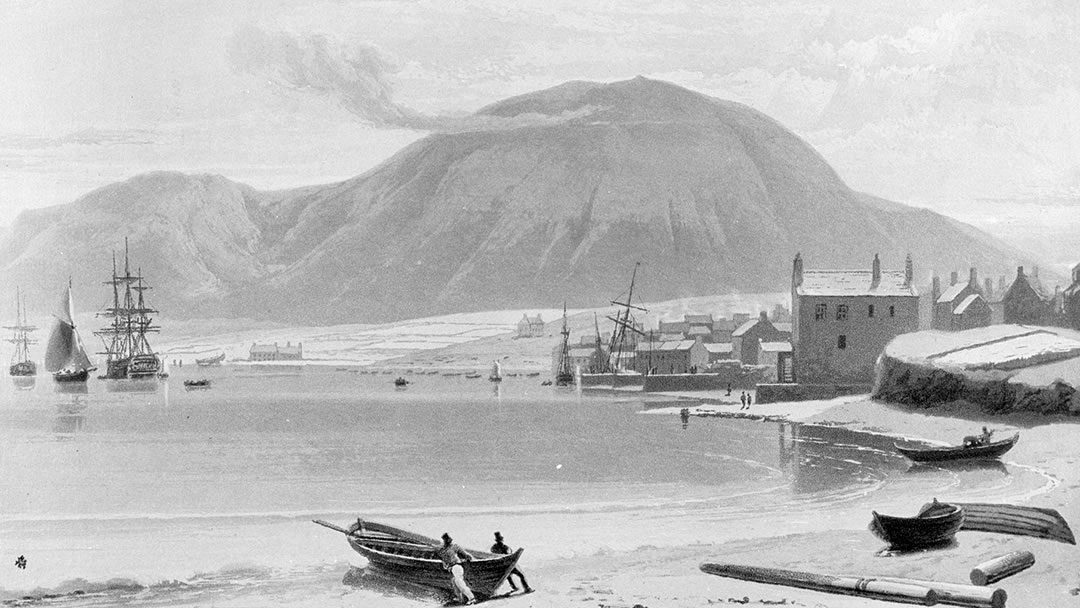

Stromness was a small cluster of stone houses under a granite hill when war broke out in Europe. Between 1688 and 1815, Britain was involved in six wars which lasted more than 60 years. Suddenly the only safe way to cross the Atlantic was to avoid the English Channel and sail around the north of Scotland.

Before long Stromness grew to be a busy seaport with inns, alehouses, and stores to provide provisions to ships. At Login’s Well (pictured above) ships would stop to take on water. Crews would then wait for a fair wind before embarking on their dangerous journey.

Hudson’s Bay Company ships regularly stopped in Stromness to take on provisions. Evidence of this can be seen today in the Labradorite found on Stromness shores. This iridescent rock from Canada was used as ballast, dumped overboard when a ship’s hold was restocked with supplies. A Canadian folk tale describes how the Northern Lights are trapped inside blue shimmering Labradorite.

1702 – Orcadians first hired

In 1702 Captain Grimington began recruiting young men from Orkney to join the Hudson’s Bay Company workforce in Rupert’s Land. This offer gave men the chance to explore the world and be paid several times the wages they would at home. They would also avoid being press-ganged into the Royal Navy. This was incredibly alluring to Orkney men used to a hard life of subsistence farming and fishing.

For the Hudson’s Bay Company, engaging Orkney men for half the wages given to London men was also alluring. However, the experiment proved so successful that each June the ships would remain in Stromness for 2 to 3 weeks, engaging 60 to 100 men.

Orkney men were used to going off to sea to improve their lot. They had excellent boat skills, were reliable, industrious, and educated. Orkney men were quiet and patient and able to endure the hardships of the wilderness. They formed good relationships with the First Nation and Inuit traders because of these qualities.

Merchants in Stromness became Hudson’s Bay Company agents to sign men into service. They operated out of buildings (the Pier Arts Centre – pictured above – and the Haven on Alfred Street – pictured below) still seen in Stromness today.

The arrival of Hudson’s Bay ships in Stromness in June was always a jubilant occasion. At the first sign of a masted ship nodding through Hoy Sound, the old cannon in the south end was fired. Evening dances were held on the ship’s deck under a rain-proof canvas awning.

Returning ships in November would land the men who had completed their service back in Orkney. They came home with news and shopping lists from those still in Rupert’s Land. Musical instruments, books, clothing, sweets, and spectacles might be requested. These would be sent to Rupert’s Land in June.

After 5 or 10 years’ service, the returning men had usually saved enough to buy a croft or farm. This annoyed the lairds, who were already losing young men they needed to work on their land. The Parish Ministers worked with the lairds, delivering sermons admonishing those who abandoned their families to sail to the Nor’Wast.

1756 – The Seven Years’ War begins

The first global war took place from 1756 to 1763. Britain and France (and their allies) fought in North America. When the war ended, France gave Canada to Britain. This is why Canada has a high percentage of French speakers and a British monarch.

1779 – On the Company’s overseas payroll 416 out of 530 are Orcadians

Though most were employed as labourers and boatbuilders, some notable Orkney men rose to high-ranking positions:

- Joseph Isbister, who joined in 1726, established a trading post inland from Hudson Bay and became head of Albany Fort and Fort Prince of Wales.

- William Tomison joined in 1760 as a labourer and served for 50 years. During that time, he pushed the company inland, founded the city of Edmonton and provided aid during a smallpox epidemic. In Orkney he founded Tomison’s Academy, a school in South Ronaldsay.

- John Ritch began work as a boatbuilder in 1836. He joined a party to map the Arctic coastline and built the explorer’s winter quarters, Fort Confidence, on the shore of Great Bear Lake. There is an island there named after him.

- In Stromness, one family business founded by a returning Hudson’s Bay Company trader is still open today. E. Flett is a traditional butcher (pictured above) set up by Adam Flett in 1876. His grandson Eric added the initial E to the firm’s name.

1806 – Mary Foubister joins

Initially white women were banned from Hudson’s Bay Company territories and many men started families with native women in Rupert’s Land. This was quietly encouraged as it offered the workers a home life and formed good bonds with the First Nation and Inuit traders. Retiring men were encouraged to settle as pioneer farmers.

At the Stromness Museum there are beautiful First Nation beadwork bags, pipes, ivory carvings, and pictures of men in jackets made by their wives.

Mary Foubister was a white woman who did undertake the crossing. In 1806, to be reunited with her sweetheart, she disguised herself as a man and made the voyage from Orkney to Hudson’s Bay with a five-year contract. Mary Foubister never found her lost love but fell instead for Orcadian trapper John Scarth. She was only discovered when she gave birth to a son, the first white child born in Western Canada.

She and her son returned to Stromness in 1809. Now known as Isabel Gunn, she found work as a seamstress and died in her nineties.

1833 – Dr John Rae joins the Hudson’s Bay Company

Born in Clestrain House (pictured above) on the shore of Orphir in Orkney, Dr John Rae was the son of a Hudson’s Bay agent. He had spent his childhood hunting and sailing, almost in preparation for the Nor’Wast.

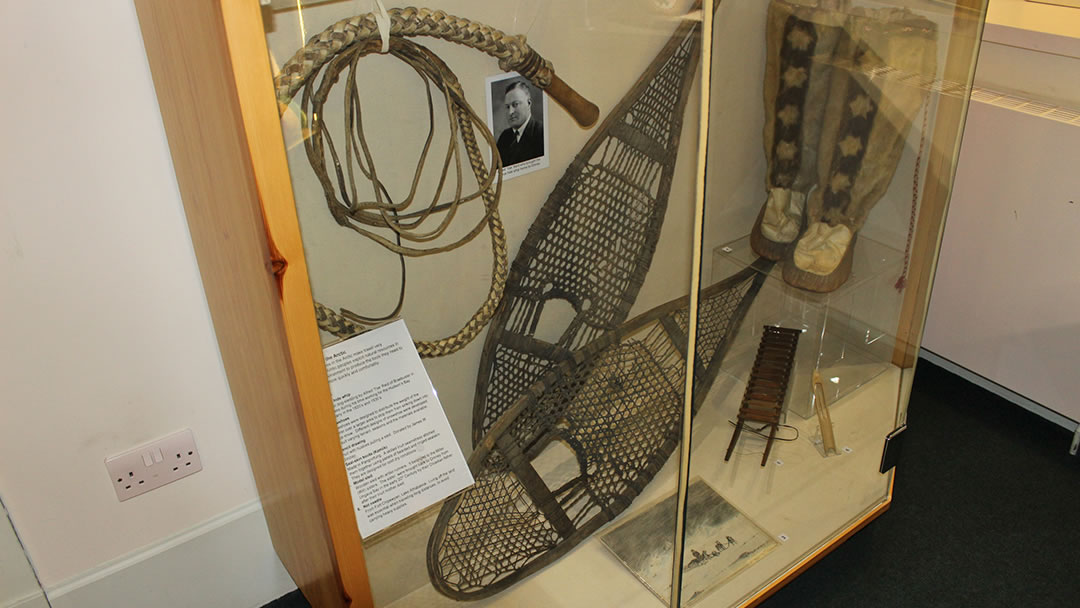

He joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1833 as surgeon clerk, and got on well with the First Nation and Inuit people. He followed their example, fashioning snowshoes, building snowhouses, and using a flat sled to carry provisions. They called him Aglooka; ‘he who takes long strides’.

Dr John Rae was able to travel swiftly through the frozen north, carrying very little and surviving off the land. He was able to survey 1770 miles of previously uncharted Arctic coastline, and found Rae Strait, the entrance to the long-sought after Northwest Passage.

His snowshoes, rifle, cloth boat, and octant (used for navigation) can be seen in the Stromness Museum.

1854 – Dr John Rae discovers the fate of Sir John Franklin’s ships

A previous attempt to discover the Northwest Passage had ended in disaster. Sir John Franklin’s two ships, Erebus and Terror, had last been seen when ropes were cast off in Stromness in 1845. As the expedition sailed into the Arctic the ice moved in behind them. The trapped crew slowly drifted to death.

Over time they succumbed to lead poisoning from the cans their food was stored in, and then to starvation and exposure. When Dr John Rae brought news to the establishment that in their final days, some of the men had resorted to cannibalism, it was met with outrage. Dr John Rae died in 1893 and is buried at St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall. There is a statue of him (pictured below) on the waterfront of Stromness.

1860 – The Deed of Surrender

After 200 years, the Hudson’s Bay Company gave Rupert’s Land to the newly created Dominion of Canada in exchange for land and cash.

1870 – The last Arctic Whaling ship arrives in Stromness

Other ships called in to Stromness to recruit men to the Nor’Wast than those from the Hudson’s Bay Company. From the mid-18th century, Arctic Whaling ships from Hull and Dundee arrived in spring. The crews took on provisions (buying beef to secure to the mast to freeze) and engaged hundreds of eager men each year.

For a month they would sail through fields of ice in the Davis Straits to hunt the Greenland ‘right’ whale. When the ‘right’ whale died, it remained afloat. Its blubber gave off huge amounts of oil, used for industry and to light homes and streets. The whale’s flexible baleen in its mouth was used for corsets and couch springs.

Orkney men were prized for their skill in small boats. They remained calm as the sea seethed about a harpooned whale. They came home with frost-nipped ears, a badge of honour, but as whale numbers dwindled, the ships needed to hunt further north, and with that, the job became more dangerous.

Some ships were crushed like matchwood in the ice, and others were trapped over winter. Those men that didn’t perish returned with scurvy and frostbite. In 1835 and 1836 a hospital was set up to treat them in Margaret Humphrey’s house (pictured above) in Stromness.

Thankfully, as demand for whale products diminished, the whaling boats stopped arriving in Stromness.

1891 – The last Hudson’s Bay vessel visits Stromness

Just as the Arctic whaling ships stopped arriving in Stromness to take on men, so too did the ships from Hudson’s Bay. Canada had become more self-sufficient and improved conditions in Orkney made the wages offered to work there less attractive. One Stromness trader, H W Leask’s draper shop (now the Royal Hotel) still supplied goods to the Nor’Wast, but this had ceased by 1913.

To enjoy lower taxes, the Hudson’s Bay Company moved from London to Winnipeg in 1970 and became a Canadian business corporation. The Hudson’s Bay Company now operates as a retail store chain in Canada and North America.

Present Day: Descendants and traces of the past

Many Orkney men remained in Canada, and some took their families back to Orkney. They are proud of their First Nation / Orcadian ancestry. In Canada, bannocks are still baked, and families retain the Orkney surnames Flett, Isbister, Linklater and Louttit. First Nation fiddlers visiting in the 1980s revealed that many Orkney tunes are still played in Canada today.

Places with links to the past, the double houses (pictured above) which belonged to whaling agent Christian Robertson, the Hudson’s Bay agency buildings, and Logan’s Well can be seen during an easy stroll through Stromness. They serve as a lasting reminder of the importance of the Nor’Wast to the Orkney Islands.

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!