Island in Focus – Eday

Amongst the grouping of Orkney’s North Isles, Eday is right in the centre. It’s a tranquil island, less fertile than others, but with much more peat. On the map Eday has a brown spine and green around the coast.

What is interesting about Eday is that, though there are many Stone Age tombs and a Bronze Age burnt mounds, there are no pictish artefacts or Iron Age brochs. It is almost as though people decided to stop living on Eday for a long time after the Bronze Age. This is because an environmental disaster occurred.

Eday has no central village and is sparsely populated. However, there is a strong community spirit amongst the island’s crofts and houses. It’s not an island that visitors flock to, which is a great shame as lovely Eday is fantastic for walking.

In Orkney, Eday is pronounced ‘eddy’. I have very fond memories of visiting Eday with my dad, who was in his sixties at the time, and we managed to walk the 7½ mile length of the island easily in a day.

We arrived in on a morning ferry run by Orkney Ferries from Kirkwall at Backaland pier in the southeast corner of the island. There was a bus at the pier, which we boarded to reach the middle of the island at Mill Loch.

Mill Loch

Mill Loch is so named because of the mill nearby which used to grind corn for the community. The loch is home to the largest concentration of Red Throated Divers in Britain.

These grey birds have a red throat, white belly, and a pin-stripe coat. They are long sleek birds, streamlined for their torpedo-like pursuit of small fish below the surface of the water. They have large, webbed feet and legs set far back, which makes them rather clumsy out of the water.

For this reason, Red Throated Divers seek out freshwater lochs, where they can land, take off, and nest close to the shore or on an island.

Known as a Rain Goose or a Loon in Orkney, Red Throated Divers have a haunting call. They lay only one or two eggs and are easily disturbed, so there is a wooden hide on the loch shore from which to observe them.

There are other birds to see on Eday, including owls and hen harriers. These birds of prey hover over the dark moorland, seeking out the small animals that hide here.

The Stone of Setter

The massive Stone of Setter is just across the road from Mill Loch. At over 4½m high with a 2m wide base, this is one of Orkney’s tallest standing stones. The Stone of Setter is said to have been over 5m high once, but it has been eroded by the weather over the years. There is a furrowed effect on the stonework underneath all the lichen. It now resembles a hand reaching up from the ground.

The Stone of Setter has proved to be tricky to date. However, the story, that a Laird erected the stone and when he did, his wife fell into the hole first, is most likely untrue.

The Stone of Setter is almost certainly prehistoric. Its position in the landscape, overlooking Calf Sound and next to Mill Loch, seems to be important. As the standing stone can be seen from the sea, some have wondered if it was placed to help boats navigate past the reefs in Calf Sound. The passageway of nearby Braeside chambered cairn points directly at the Stone of Setter.

Early settlers

Eday has been occupied for 6,000 years, and the early settlers were farmers. They grew cereal and used saddle querns to grind their golden harvest. They also kept sheep or cattle in circular enclosures like the Fold of Setter which can be found near the standing stone.

Evidence of the early settlers can also be seen in the communal chambered tombs on Eday. Chambered tombs have partitions which create stalls like those in a cow shed. In Eday there may have been a tomb for each community.

A walk from the Stone of Setter will take you across moorland (with boardwalks over boggy ground), past Braeside Chambered Cairn, which is missing its roof, and Huntersquoy Chambered Cairn. Like Taversoe Tuick on Rousay, Huntersquoy is on two levels, but is usually flooded.

Keep on going to reach impressive Vinquoy Chambered Cairn, built into the slope of Vinquoy hill. This fascinating tomb from 2,000 BC resembles Maeshowe on the Orkney Mainland. After crawling down the long entrance passage, visitors can stand up inside the 3m high main chamber, and peer into the 4 side cells.

There are other tombs in Eday. Hidden in the heather south of Eday’s airport is Church Chambered Cairn (named because of its proximity to an abandoned church) and a beautiful spiral incised stone was found in here. It can be seen in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

An Environmental Disaster

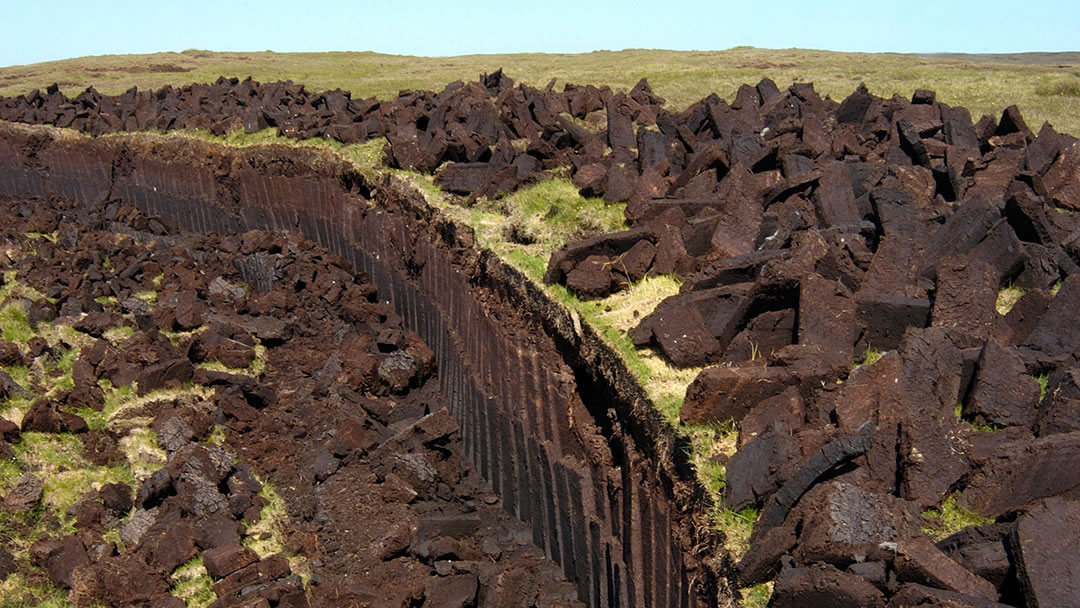

What is interesting about Eday is that, though there are many Stone Age tombs and a Bronze Age burnt mounds, there are no pictish artefacts or Iron Age brochs. It is almost as though people decided to stop living on Eday for a long time after the Bronze Age. The peat that covers much of the island offer some clues.

On Eday many Bronze Age field boundaries were found buried underneath the blanket peat, indicating that the land was fertile and densely settled in the Stone Age and Bronze Age and then an environmental disaster occurred.

Peat is the accumulated remains of plants which have not decomposed due to water-logged conditions. It formed during what was thought to be a cold and wet period (Scientists think large Icelandic volcanic eruptions in 1628 BC and 1159 BC may have been to blame). Farmers must have struggled as the dust damaged their crops and the ground turned to bog. As they continued farming, greater damage occurred to the land. Disease, famine, conflict, and migration usually occurs during such a dramatic change.

Famers in other areas of Orkney would have struggled with the wetter climate too. However the forming of peat was not so extensive on other islands. There are only one or two glimpses of life in Eday between 1000 BC and 1600 AD. Eday has Old Norse placenames but doesn’t feature in the Sagas. With little arable land, the Eday residents of 1600 were poverty stricken.

As transportation improved, many left to find work on the Orkney Mainland and in the Nor’Wast. There were 947 residents in 1841, 198 in 1958, and 139 by 1981. Around Eday we saw a great many derelict crofts.

The Red Head

Eday has other resources than farmland though. The island is known for its Middle Old Red Sandstone rocks. After a 2 mile walk from Vinquoy Chambered Cairn, there is the dramatic cliff called the Red Head on the northern tip of Eday. This is a large section of exposed sandstone.

Eday sandstone is so hard that it does not erode to form seabird ledges. This made this yellow and red coloured stone excellent for building.

At Fersness on the west side of Eday, there was a quarry above the shore which had its own pier. Many yellow stones were hewn from that quarry and exported to Kirkwall for the construction of the doorways of St Magnus Cathedral. The red sandstone used for the rest of the Cathedral came from the Head of Holland, just outside Kirkwall on Inganess Bay.

Stone from Fersness was also sent to build Scalloway Castle and Balfour Castle. The Eday stone industry came to an end with the arrival of cheaper concrete blocks, and in 1952 and 1953 when black winter storms demolished the pier at Fersness.

At the Red Head there is a spectacular view of the other North Isles and of the Calf of Eday.

The Calf of Eday

The Calf of Eday is a smaller island (a ¼ mile wide) off the north of Eday. ‘Calf’ in Old Norse describes a small island like a calf next to a mother cow. The currents in Calf Sound between the island and Eday are strong. On the Eday shore there is a lighthouse.

The island is uninhabited now, but those who venture across will discover long chambered tombs, an Iron Age roundhouse from 600 BC and fields littered with ards (Neolithic stone ploughs used to break the soil). On the shore, with one end in the sea, there is a salt works which operated in the 1630s. Salt crystals, for preserving food, were collected by evaporating seawater using peat fires and vents.

The Calf of Eday has vast numbers of breeding seabirds on the Grey Head. It is also home to Orkney’s largest cormorant colony.

Carrick House

Along the coast and facing the Calf of Eday, Carrick House was built in 1633 by John Stewart, brother to Patrick Stewart, the brutal Earl of Orkney and Shetland. Over the years it has been owned by a succession of Lairds and today remains a handsome building. The current owners kindly open Carrick House to visitors by appointment in the summer.

Through the years the Lairds of Eday brought about improvements to the island. They upgraded the roads and piers, became shareholders in the inter-island ferries and brought wealth to the islanders through land improvements and new industry, such as collecting kelp and exporting peat.

The relationship between Lairds and their tenants was not always amicable though. A dispute over a cargo of washed-up wood culminated with wriggling sackfuls of rabbits being emptied into the enclosed garden of Carrick House!

Perhaps the most well-known story about Carrick House involves the pirate, John Gow.

John Gow

John Gow was brought up in Stromness and went to sea in 1724. He began misbehaving immediately and attempted to overthrow the captain of the first ship he sailed upon, though too few men were willing to join him. On his next ship, Caroline, Gow, and a group of men murdered the captain and his three officers off the Iberian coast. They changed the name of the ship to Revenge and began capturing ships and their crews and taking valuables where they could.

After a time, with the authorities in pursuit, the Revenge sailed into Stromness harbour. John Gow disguised himself as a shipping trader and struck up a romance with Helen Gordon, a local lass. They took vows holding hands though the hole in the Odin Stone.

Some members of Gow’s crew had been in fear for their lives and saw the stop in Orkney as their chance to escape. The authorities were alerted, and the pirate ship set sail again.

Gow first raided the Hall of Clestrain in Orphir but when he attempted to attack Carrick House, the Revenge was driven against the Calf of Eday. John Gow was captured and held in Carrick House until his trial in London. Visitors can still see Gow’s bloodstains on the floor and the bell from the Revenge in Carrick House.

John Gow was sentenced to death and hanged at Greenwich. It is said that Helen Gordon travelled to London and held his dead hand to break the vow between them.

Eday Peat

Much of Eday’s land is covered in peat. In the summer peat is cut into small briquettes and dried in the sun, in stacks called ‘roos’. When the peat is hard it can be burned like a coal on the fire. In the old days peat was important for providing winter warmth. Eday peat was called ‘inkies’ because it was so black and of such good quality. The enchanting aroma of burning peat is similar to woodsmoke but with a rich earthy quality.

Eday became an exporter of peat to peatless islands. The Islanders from Sanday and North Ronaldsay would sail to Eday and cut peats in exchange for oats or barley. Peat-cutting is hard work though and this arrangement ended when the transport of coal improved.

After the First World War, the Laird, who had a good relationship with the owner of Highland Park, saw an opportunity for Eday. In the early stages of distilling whisky, the damp malt must be dried over a peat-heated fire, and this enhances the flavour of the end product. The Laird contacted distilleries down south and soon vast quantities of peat (900 tonnes a year) were shipped from Eday to make Glenmorangie, Glenlivet, Old Pulteney and Scapa whisky. Railway tracks, used for carting peat downhill can still be seen on the island.

During World War 2 a shortage of labour made it difficult to continue supplying peat on such an industrial level. A more mechanical approach was suggested, but given peat takes 100 years to grow 10cm, the decision was made to leave the island as it is. These days the Islanders only cut small amounts of peat for their own fires.

Other Eday places to see!

As my father and I walked back towards the south end of the island and Eday’s pier, there was still plenty to see.

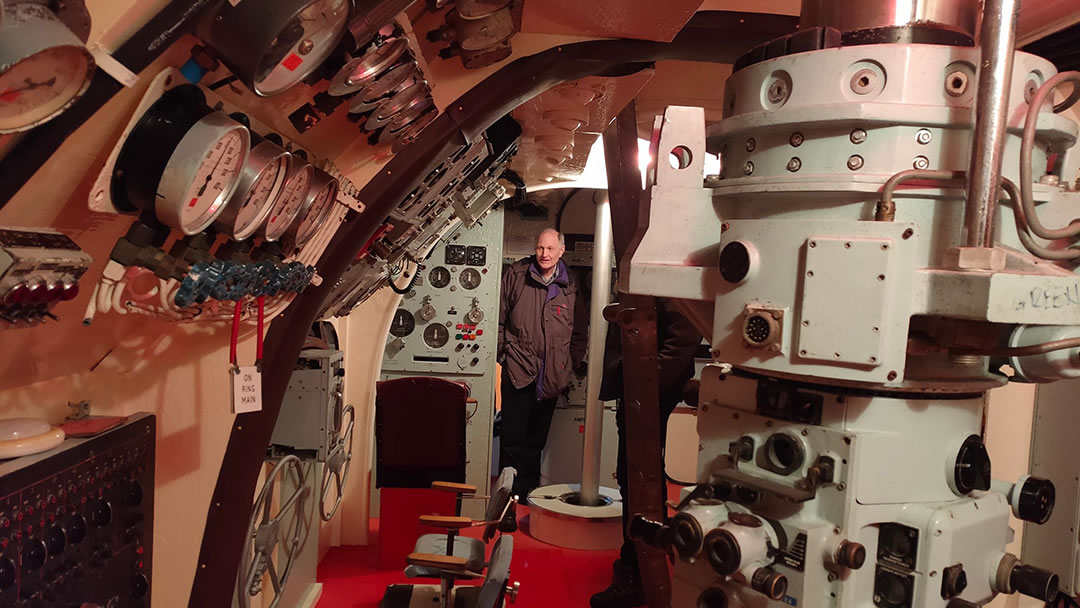

Mike Ilett’s submarine display is housed within the Old North School. This amazing display of submarine equipment from HMS Otter and other submarines is almost like being on board the real thing, deep below the waves.

Down the road there is a well-stocked shop on the island run by Eday Community Enterprises. The Hostel on Eday is also community-owned.

Walk further south still to explore the Eday Heritage and Visitor Centre in the beautifully converted Old Baptist Chapel. Inside there is an exhibition area and café, though should you find the café closed, there is a ‘help yourself’ hot drinks facility available.

In the centre of Eday the island narrows dramatically. We passed by the island airstrip called London Airport. The name comes from the Old Norse ‘Lund-inn’ meaning woodland, and there were trees here in Norse times. Nearby at Mussetter ancient tree roots can be glimpsed when the tide is low.

Other fine places to explore in the south of the island include Ward Hill, which at 101m is Eday’s highest point. The beaches at the Sands of Mussetter, the Bay of London and the Sands of Doomy are very fine. Neolithic houses were recently discovered at Green, south of Backaland pier.

Along the south shore there is a green mound which is being eaten by the sea. This is the Castle of Stackel Brae, which was once a fine house, possibly from Norse times or possibly a multi-period site.

Out in the seas around Eday

In the sea to the north of Eday there is a tidal energy test site at the Falls of Warness, the first of its kind in the world.

Half a billion tonnes of water race through here an hour, which makes it a perfect place to test devices that can turn that energy into electricity. Sometimes these devices can be seen on the surface of the sea, but often they are bolted to the seabed. The surplus energy from tidal devices and from the community wind turbine on Eday is turned into hydrogen which provides electricity for the inter-island ferries.

Out in the waters between Eday and Westray, the island of Faray has been uninhabited since 1946. The island is now home to sheep and contains interesting archaeological sites. There is a postbox on Eday where mail for the Faray Islanders was once delivered.

Also, in the bright blue sea off Eday, the islands of Seal Skerry, Muckle Green Holm and Little Green Holm are important breeding grounds for grey seals. 650 seal pups are born there every year.

My father and I were in high spirits as we headed towards Backaland pier to meet the evening ferry back from Eday to the Orkney mainland. I’ll remember my dad’s good company that day. He was a keen photographer, and his camera was used often on Eday, especially as we stood below the towering Stone of Setter and savoured watching Red Throated Divers on Mill Loch.

Eday is a wild island with a dramatic history to unearth beneath its peaty surface. It is well worth taking the time to explore this hidden gem amongst Orkney’s north isles.

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!