Inside Strathnaver Museum

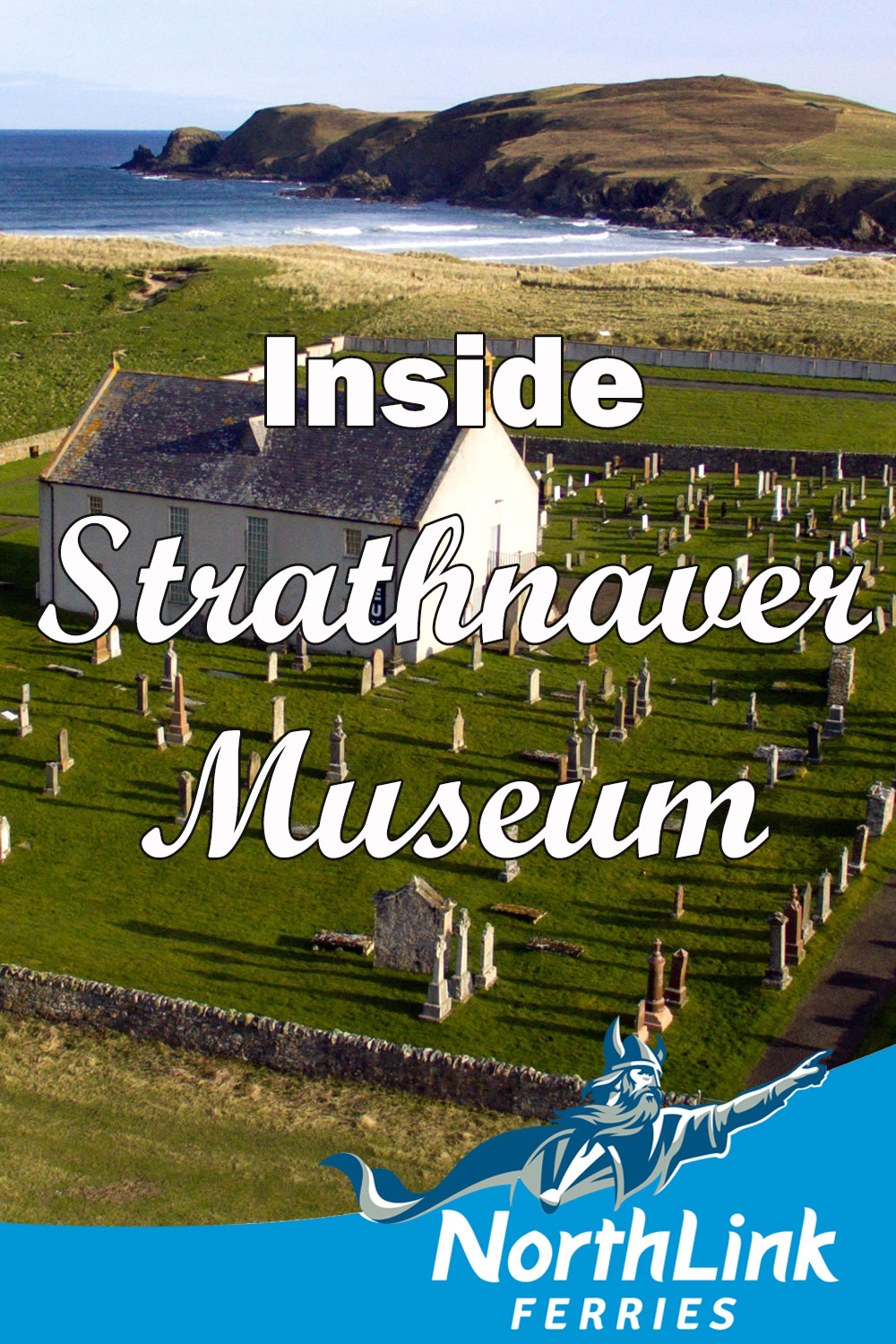

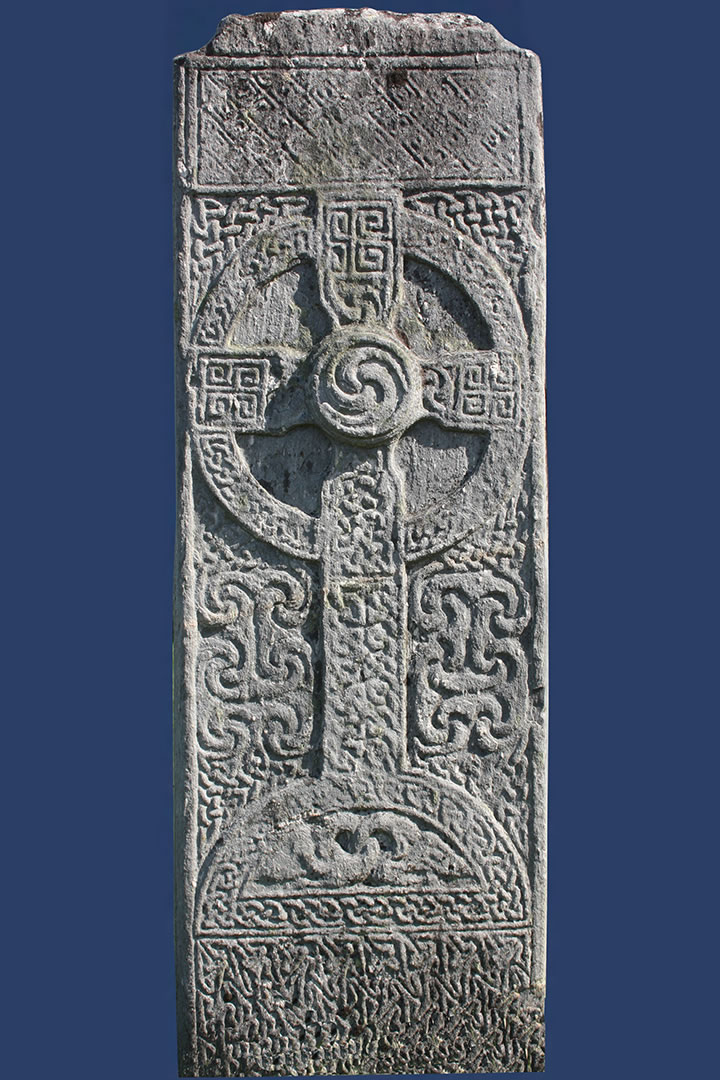

Located just 30 miles from Scrabster, close to the sandy beach at Farr Bay in the former Parish Church of Columba in Bettyhill, Strathnaver Museum is a truly fascinating place to visit. Opened in 1976, it hosts a range of exhibits, including artefacts from the Norse and Gaelic people who lived in the area and Mackay memorabilia belonging to the Clan Mackay Society.

Strathnaver Museum is located in a former church which has a long association with the story of the Highland Clearances.

However, Strathnaver was one of the places most affected by the Highland Clearances, and that story is told here, as explained Fiona Mackenzie, Development Manager of Strathnaver Museum.

Q. What can visitors expect to see when they visit the Strathnaver Museum?

A. The main story we tell at Strathnaver Museum is that of the Highland Clearances. However, we don’t just tell the story of the Highland Clearances. The building hosts a varied and important collection of objects and stories which tell the story of the people who inhabited the area for 8,000 years. The collections range from prehistory to the modern day.

We also house the only Clan Mackay Centre in Scotland so we get a lot of Mackay visitors returning from all over the world. They come from places like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and a lot from Holland. This is because a lot of the Mackays went out as mercenaries during the 17th century and fought for the protestant cause, first under Christian IV of Denmark and latterly under Gustavus Adolphus, the king of Sweden during the 30 years’ war.

It’s very interesting working here – we get a lot of very diverse visitors.

Q. Can you tell us about the Highland Clearances?

A. Thousands of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands were removed from their homes. This happened mostly between the years of 1750 to about 1860.

The main motive behind this was that the landlords who imposed the removals or clearances had a desire for agricultural improvement which was influenced by an economic desire to increase their income through rents.

The landlords enclosed the open fields which had been laid out in runrigs and used for shared grazing in communal townships. These were replaced by large sheep farms which were rented to one individual, and the landlords received a much higher rent from them.

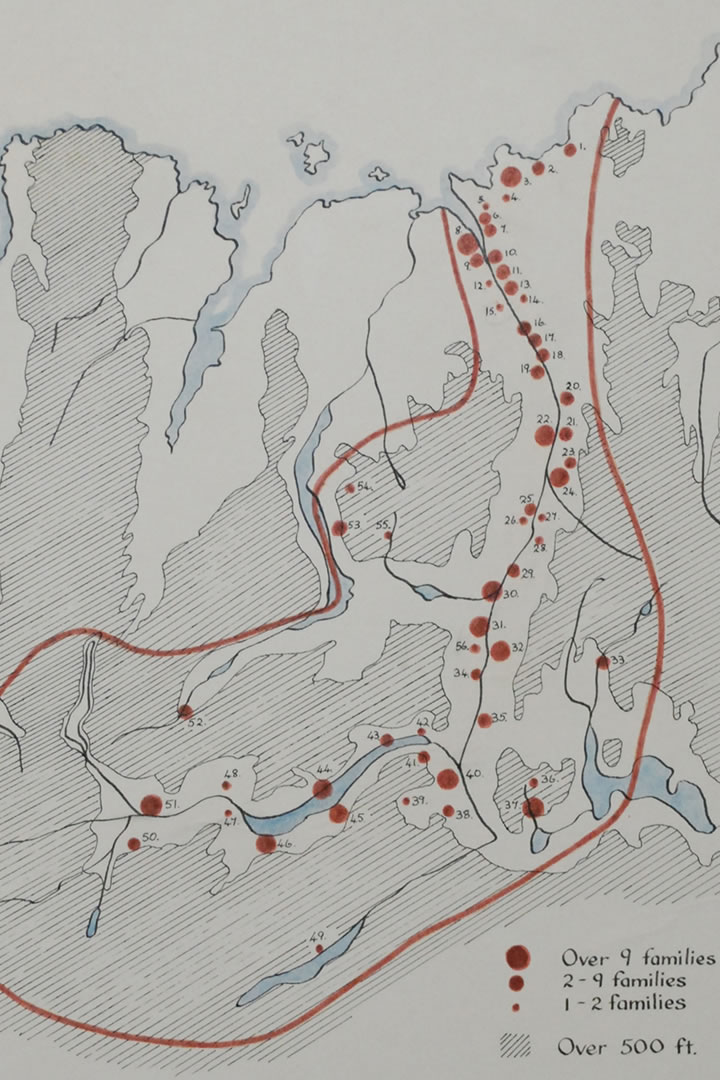

Commercial sheep farming began in Sutherland in the 1770’s and in Strathnaver the removals took place between 1807 and 1822, with the main removals taking place from 1814 to 1819. In Strathnaver glen alone about 350 families or about a thousand people were removed from their homes to make way for a handful of large sheep farms.

Q. Where there other factors that influenced the clearances?

A. Often the landlords had large debts and they were becoming used to sustaining a particular lifestyle in London which of course costed money.

So for greater profits, the communal aspect of the land use previously employed by the tenants was replaced by these large scale pastural farms. The removed tenants were given alternative tenancies in newly created crofting communities but these were on marginal lands, divided into small parcels of land. These new crofters were expected to supplement their income through other activities such as fishing, the kelp industry or lime production.

The movement of people occurred in two phases. That would have been the first phase. Then the second phase saw assisted passage being offered when these now overcrowded crofting communities struggled to support themselves.

There were a number of forces that lead to that depression; these included the fall (from 1815) in the price of cattle and the growing pressure on the land itself. More families had to rely on seasonal work through the kelp industry and that also began to decline. There was fluctuation in the fishing and then the potato famine which lasted from 1846 to 1856. These all had an influence on people leaving. They either emigrated abroad or moved to the south.

Between 1852 and 1857 about 16,000 people were assisted to cross the Atlantic from the North West Highlands alone. It’s incredible when you think about how many people used to live in what now can be seen to be deserted glens.

Q. You mentioned Clan Mackay – can you tell us about them in relation to the clearances?

A. The area that Strathnaver Museum serves is known as Mackay country. It covers an area of about 2,000 square kilometres. However, the Highland Clearances put the final nail in the coffin for traditional clan society.

Clans were ruled by one family with a chief drawn from that family. Then the kinsfolk and all the others who made up the clan lived in these agricultural townships.

The land would have been leased to a tacksman who was often a cousin of the chief. The tacksman then rented it to farmers who in turn employed cottars to help cultivate it. The clan itself would have owed allegiance to the chief to provide fighting men to serve him in the military. The chief was seen as a paternalistic figure, but when the clearances took place, his connection to the people would have been severed.

In Mackay country a lot of the land was sold to Sutherland estate. In 1790 John Mackay of Strathy sold the Strathy estate to an Edinburgh lawyer who then sold it on to the Sutherland estate in 1813. Then Armadale was sold in 1812, Strathalladale was sold in 1830, and Durness was sold in 1829. So the paternalistic link between the clan chief and the people was well and truly severed by that point.

Q. Could you describe the houses that the people of Strathnaver were cleared from?

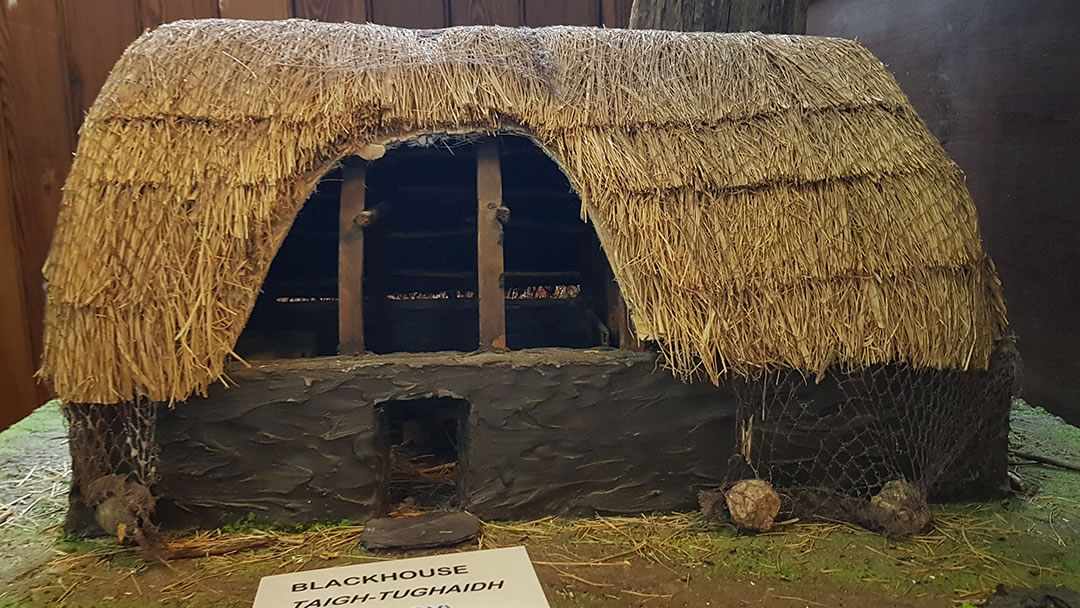

A. The people would have lived in ‘blackhouses’, which were also known as longhouses. These were typical dwellings found in the townships prior to the clearances.

The name highlights the blackness inside the building. There would have been a hole in the roof which acted as a chimney. However it would have been very dark inside as blackhouses had no windows! The dwelling would also fill with smoke from the peaty fire in the middle of the room. People would crowd around the fire to cook, to eat, to dry their laundry, to tell stories, knit, sew, play music and to sing.

The chairs and stools at that time had very short legs and this was so that people could sit below the smoke which rose to the roof. We have a couple of examples of these in Strathnaver Museum.

The cruck frame which made up the roof base would have been made from fossilised moss fur which was dug out of peat bogs. Then the walls themselves were constructed with large stones at the base and then blocks of peat higher up. The floors were usually clay with straw on top and the roof would have been thatched. This would have needed to be replaced quite regularly.

Humans and animals would commonly share the dwelling, with only a partician separating them. It would have been quite warm with all those bodies inside. The materials used were designed to absorb the heat from outside whilst maintaining it within the dwelling as well. So blackhouses probably were quite cosy, although also quite smelly!

Q. Is it possible that the clearances encouraged those living in the North Highlands to migrate across the Pentland Firth to Orkney?

A. Yes, it’s quite possible. In 1819 on the Sutherland estate there were about 3,300 people that were removed. The vast majority of those were resettled on the estate, and some moved to adjoining properties. However 660 of those migrated to neighbouring counties and it’s likely that would have included Orkney.

Seasonal migration was well established by the 18th and early 19th century. That largely involved younger people going to fishing ports such as Orkney to become seasonal workers for the herring fishing. Following the mini famines in the mid-1830s and the potato famine in the 1840s and 60s more people began to take up seasonal employment.

Q. To what extent have the Highland Clearances impacted Scottish culture?

A. It certainly had a big impact on Scottish culture not necessarily just at home but also on the distribution of Scottish culture on the rest of the world.

Highland clan culture is rooted in traditions of family and fealty with the clan chief as the paternalistic protector of his people. However, following the Battle of Culloden and the 1746 Act of Proscription which outlawed tartan, bagpipes, and the teaching of Gaelic amongst other things, that culture had already began to be eroded.

The Highland Clearances would have impacted directly on the traditional way of life of the people who inhabited the glens. It changed from them being a subsistence peasantry to being a proletariat depending on other forms of employment to sustain themselves.

For those who emigrated, life in their new home could have been closer to what they had experienced previously, especially compared to what their contemporaries would have experienced when they moved to the industrial south.

Those who emigrated took their culture with them and created communities in Canada, America, New Zealand, Australia which were very much influenced by their culture.

You can see this influence today in place names but also in the amount of Highland Games, clan societies and tartan days that take place. I see it in the sheer number of people that come back to Strathnaver Museum who see themselves as being Scottish because of that link.

Q. Why is it important for us to remember the Highland Clearances?

A. I think it is important today as when we visit the inland parts of Sutherland specifically, it is often thought of as a remote, wild and empty place.

However at one point it was full of people. In 1755, 51% of Scotland’s population lived in the Highlands but by 2013 that was only 4% of the population. I’m not sure what it is today but it is probably a little less than that. Recent figures from the Highland Council have estimated by 2041 the population of Sutherland will have fallen by a further 21%.

I think it’s important if the Highlands are to increase its population, that heritage and tourism are key drivers to that, providing opportunities both for learning and also to support the local economy.

Q. Are there any initiatives currently to help bring younger generations to the Highlands?

A. A recent Highlands and Islands Enterprise report showed that there are increasing numbers of young people who do want to live and work in the Highlands and Islands. The initial study was done in 2014 and the number saying that they would like to remain has increased by about 10% to 46% of young people which I think is really encouraging.

There are more opportunities within the area to study which has contributed to that increase as well as other initiatives such as ‘Developing the Young Workforce’ which is the Scottish Government’s employment strategy to better prepare young people for the world of work. These are employer led regional groups which are acting to connect employers with education providers.

Strathnaver Museum seeks to bring social and economic benefit to the local community by providing opportunities to access our collection. Our future vision is to create a heritage hub for North West Sutherland which will support the local economy while also providing valuable employment opportunities, and training and learning opportunities too.

Q. What do you think is the most significant item in the Strathnaver Museum?

A. I think the most important item in our collection is the biggest – the building itself! Strathnaver Museum is located in a former church which has a long association with the story of the Highland Clearances.

It was in this church that the Reverend David Mackenzie was obliged to read out eviction notices to his congregation. Later on the building also hosted the Napier Commission where evidence was given by the crofters and the cottars depicting the treatment they had during their removals.

We have testimonies on the wall and its quite emotive reading the words and imagining that, a couple of hundred years ago they were said in the building itself.

Q. Do you have a favourite exhibit?

A. I think probably one of the more charming aspects of Strathnaver Museum is how rooted it is within the community. The Museum originated as a community response to an identified need to retain academic research within the area for the benefit of the local community.

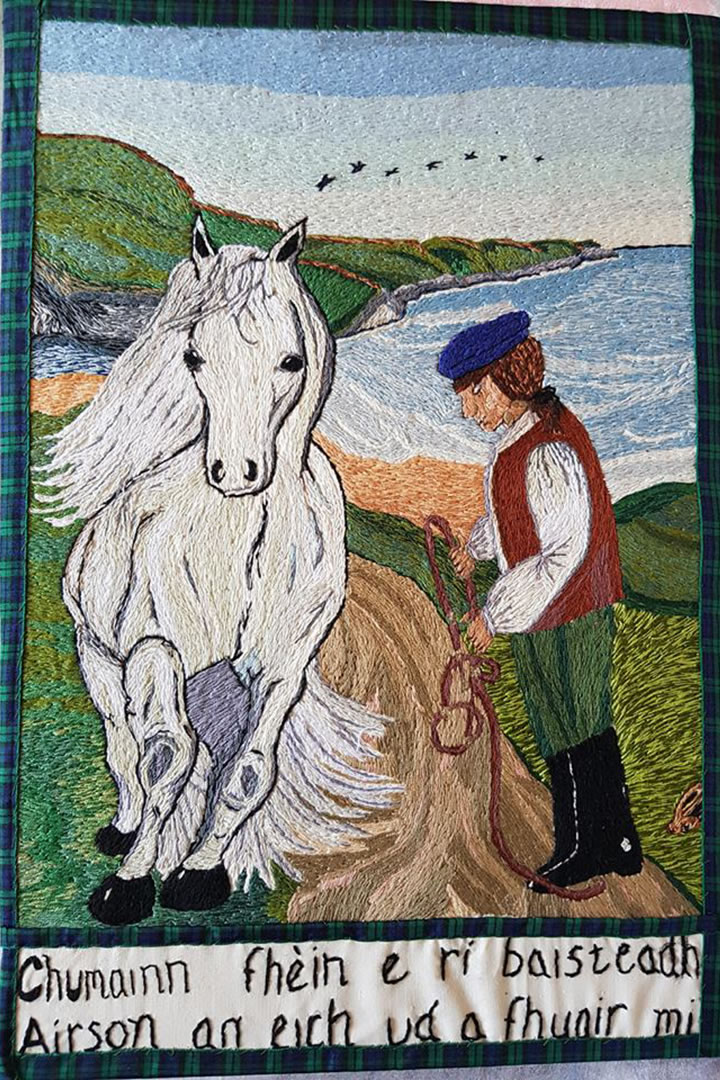

This is the ethos that remains today and involving the local community in telling their own story is probably what makes the museum so very special. For this reason I really love the exhibits that have been created by the local people to interpret their own story.

The Rob Donn Mackay exhibition was launched in 2018 and is currently on display in the museum. It explores the work and life of the renowned 18th century Gaelic Bard, Rob Donn, and it is an eclectic mix of art and craft work which has been created by the local community. It gives a really rich depiction of 18th century society in Mackay country.

Q. What current projects are you working on at the moment?

A. The main one is the refurbishment of the building itself; this is something the museum board have been working on for quite a long time. The building was built in the mid 1700’s and is in urgent need of repair and refurbishment.

We’ve been working hard to secure funding to realise the ambition of turning Strathnaver Museum into a world class visitor attraction which will enable us to display our objects better and the story that we tell.

At the moment we are securing the last elements of the funding and hope to be in a position to start work on the project in late 2020. That will see us build an annex building to the rear of the graveyard which will improve the amount of space we have. It will also allow us to house an agricultural exhibit, give us an accessible public toilet, improve the retail space and create a research room as well. Then people will be able to look at the archives and information that we have and continue to gather though our community research projects.

Alongside that there will be an extensive program of activities which will accompany the capital work. These very much focus on the Highland Clearances but one of the other projects that we have just recently received funding for is to create reminiscence boxes. This has been inspired by the Highland House of Memories app project led by High Life Highland and Liverpool Museums. The boxes will complement the House of Memories app which can be loaned out to local care homes or other community groups working with older people, particularly those that have dementia. This will help carers support the people they are looking after.

We also aim to create more special exhibitions in the communities that we serve. The community itself is over 2,000 square kilometres so this makes it quite challenging but fun also!

To find out more about the Strathnaver Museum and to plan your visit, please visit the Strathnaver Museum website at https://www.strathnavermuseum.org.uk/

By Hannah Richards

By Hannah RichardsA University graduate from New Zealand with strong ties to Orkney and the East Coast of Scotland. Hannah enjoys discovering new places and is looking forward to travelling around Europe. She has great appreciation for history, music and art.

Pin it!