The Scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet

100 years ago, the German navy did the unthinkable: it deliberately sank 52 of its own ships in one day.

As a result of the actions on that day, it is believed that nine Germans died. They were the last to fall during the First World War.

The scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow on 21 June 1919 was a deliberate act of sabotage carried out on the orders of Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, who feared that the fleet would fall into the hands of the victorious Allied powers of the First World War.

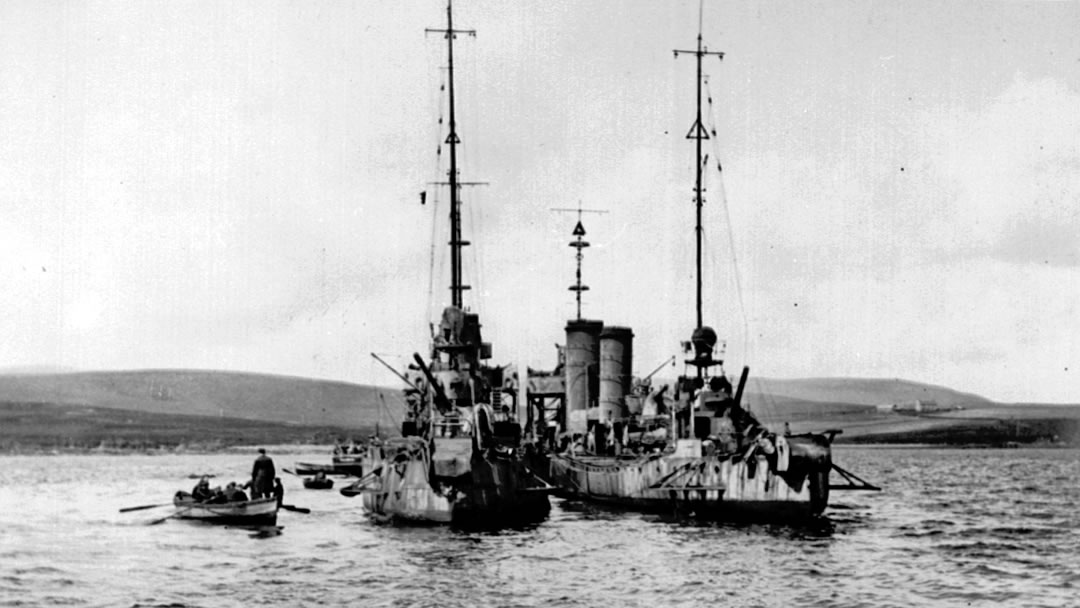

After the fighting of WW1 ended in late-1918, the entire German fleet was “interned” by the Allied forces and eventually moved to the sheltered natural harbour of Scapa Flow. There were 70 ships in total, including nine formidable battleships, 49 destroyers and five battlecruisers and each was held at Scapa Flow while their fate was decided in Versailles.

Until a decision was reached, German sailors were kept on board their ships, not knowing if the vessels would be broken down for parts, or shared amongst the victorious navies they so furiously fought during the war.

The ships were never surrendered and remained the property of the German government during their stay in Orkney but commanders weren’t kept up-to-date with the latest news from France. Instead, they relied on old newspapers with outdated updates from the peace conference.

When the original deadline for the peace talks approached on 21 June, with no update, Admiral von Reuter assumed they had failed and the Royal Navy was preparing to seize the fleet.

Unbeknown to the Admiral, the deadline for talks had been extended. However, it was too late.

A man of duty and honour, the Admiral vowed to his men that he would not allow the fleet be boarded and sent letters to all his commanders with news of his plan and secret instructions. At around 11:20am on 21 June 1919, the Admiral transmitted the code “To all Commanding Officers … Paragraph Eleven of to-day’s date” from his flagship Emden.

One by one, from north to south, the ships that were spread across Scapa Flow received the message. Below decks, sailors started opening seacocks – valves that allow water in – and smashed pipes.

It wasn’t immediately clear what was happening but after a couple of hours, it became obvious that the Germans has deliberately sunk their ships.

As the Germans escaped their sinking ships in small boats, a small force of Royal Navy sailors struggled to work out what to do. Most of the Royal Navy in the area had taken advantage of the good weather and sailed out for training – something Von Reuter used to his advantage.

Unfortunately, in the confusion, a boat of unarmed Germans didn’t fly the white flag of surrender and was fired upon by the British. This disastrous mistake was witnessed by a group of schoolchildren from Stromness who were on a trip to see the German fleet. As a result of the actions on that day, it is believed that nine Germans died. They were the last to fall during WW1.

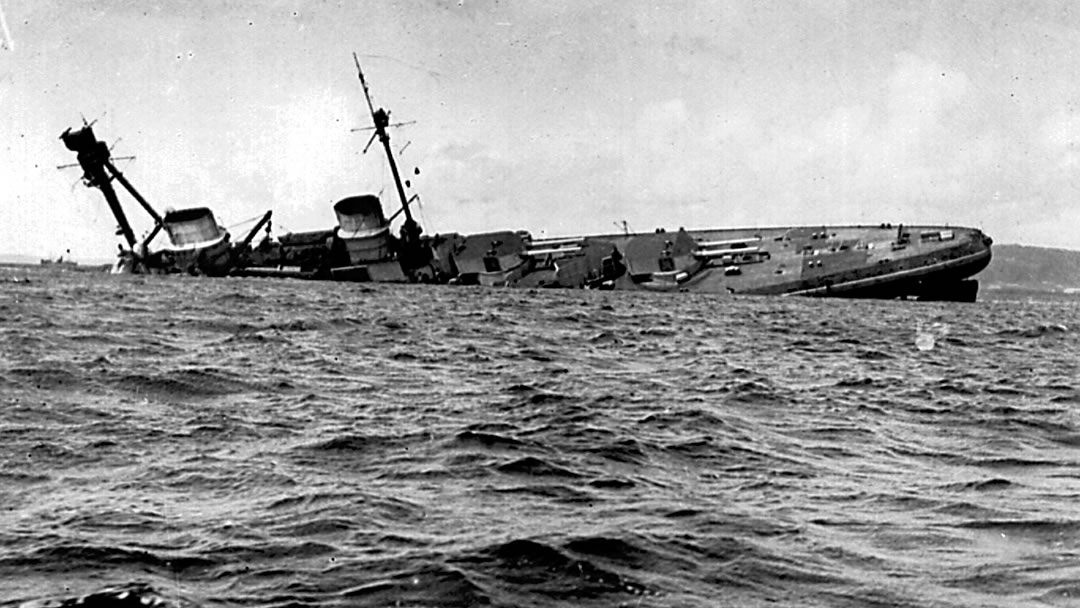

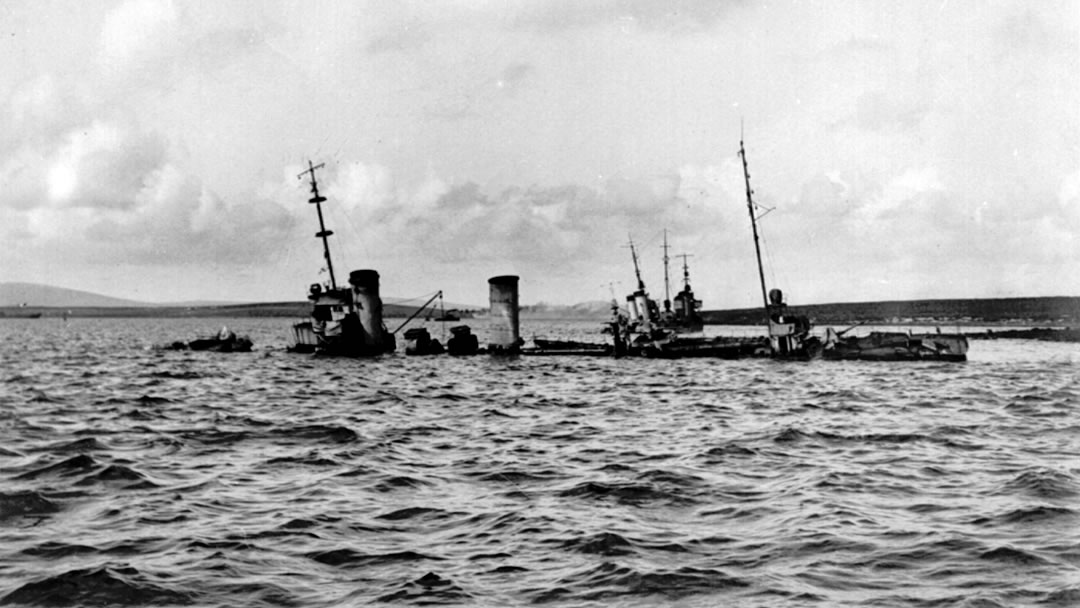

By the evening of the day, almost the entire fleet has disappeared beneath the waves, with the mammoth Hindenburg battlecruiser the last to sink. Royal Navy sailors were successful in beaching some of the sinking ships but the vast majority lay on the seabed.

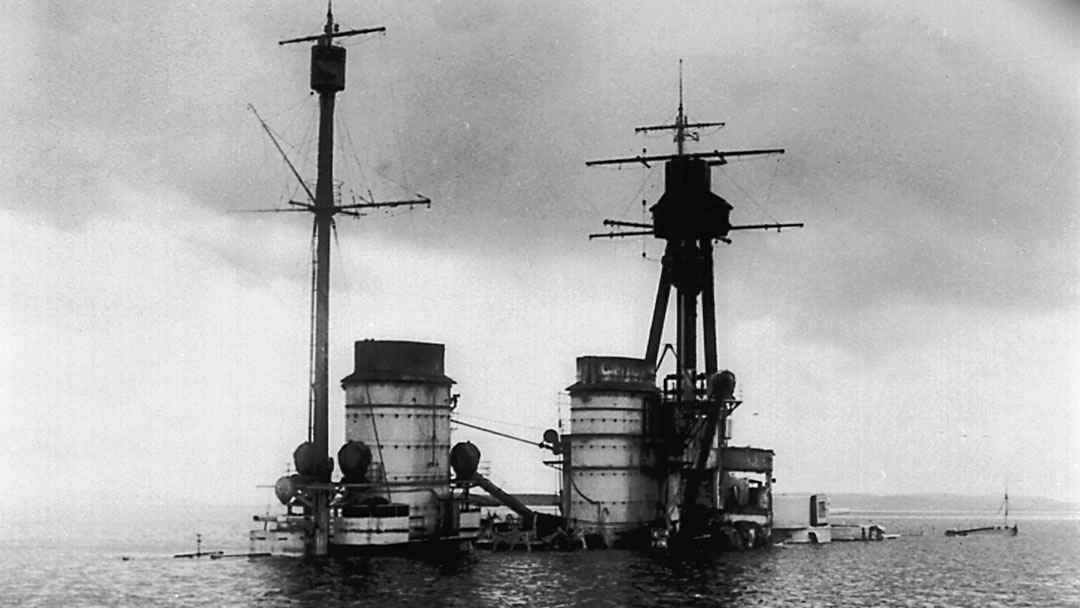

Some of the ships were so large and the water so shallow that their funnels and upper works were visible above the surface. It was decided that those that had sunk were to be left where they lay. The aftermath of WW1 had seen an abundance of scrap metal and plenty of other warships were being broken up.

Despite the Admiral’s best efforts, the ships that were saved were eventually dispersed to the allied navies and it wasn’t until complaints from locals that salvage works really got underway in the 1920s and 30s.

At the time, the British considered the scuttling an act of aggression but in Germany it restored a sense of pride during a period of national humiliation.

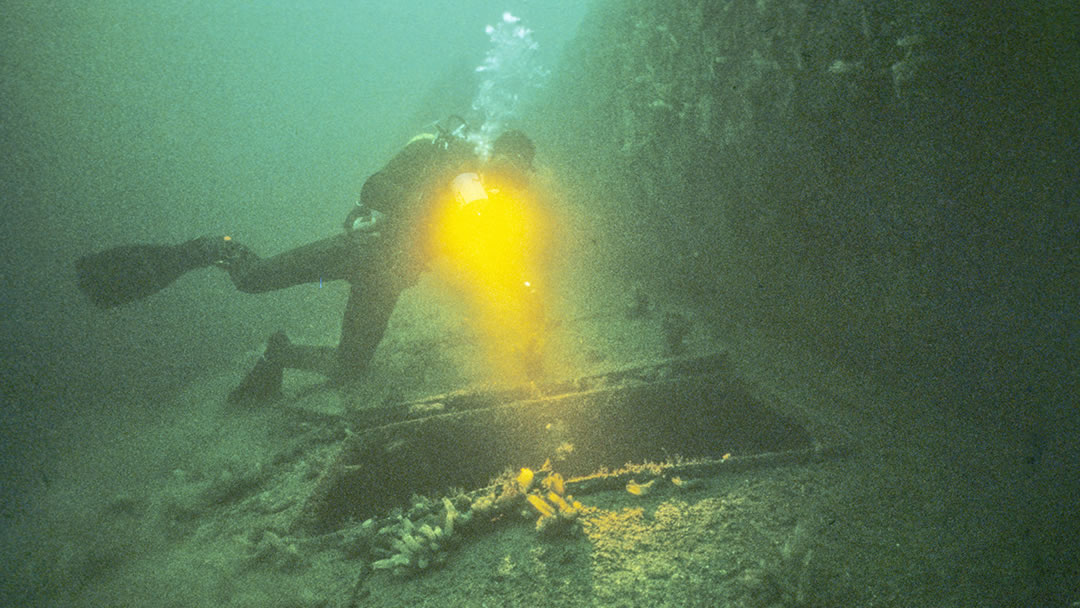

Seven wrecks are all that remain at the bottom of Scapa Flow. They are now classed as scheduled monuments with divers needing a permit to explore these unique memorials to the one of the world’s worst conflicts.

By Jamie Bannerman

By Jamie BannermanBorn and bred in the North-east of Scotland, Jamie is a PR manager at Weber Shandwick. He is a keen traveller and enjoys exploring new places and hidden treasures across Scotland or in far-flung exotic destinations. Jamie has an in-depth knowledge of Aberdeen and also enjoys hillwalking across the North-east with his dog Hendricks in tow.

Pin it!