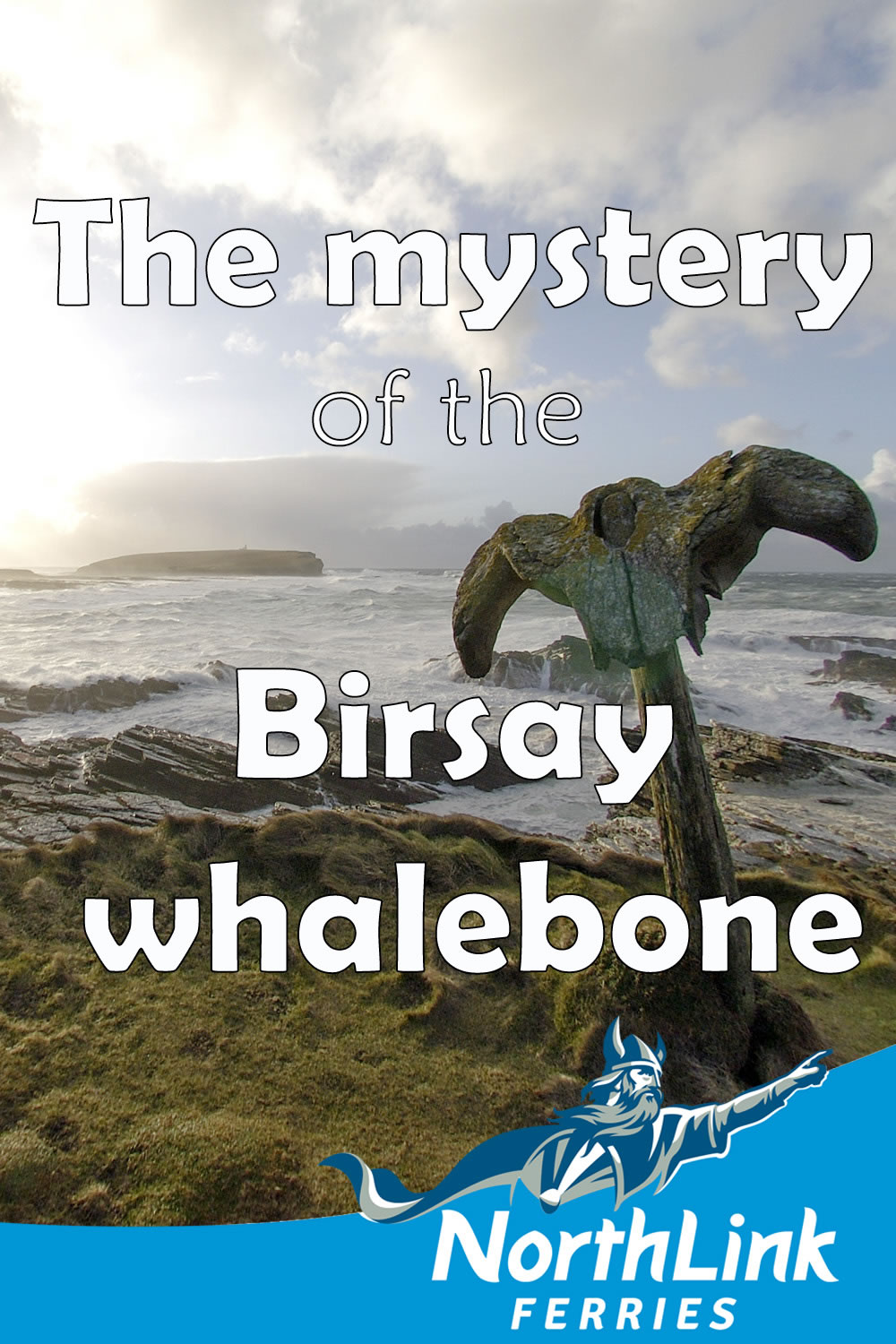

The mystery of the Birsay whalebone

There’s a great walk to be had in Birsay and at the end of it lies a great mystery! Most visitors park at the Point of Buckquoy and walk across the causeway to the tidal island, the Brough of Birsay.

These days a whale being washed ashore would be considered an ecological disaster, but at that time it was like a harvest to the folk of the Northside

However, we’d recommend walking ¾ mile towards Northside to Skiba Geo (also known Skipi Geo, Skibba Geo or Skibi Geo).

It’s a lovely coastal walk with seals, rockpools and many birds! When you reach Skiba Geo there’s a 19th century fishing hut above a stony shore. There’s a staircase cut into the cliff here and nousts – boat shaped hollows in the ground where fishing boats were drawn up high from the shore and stored over the winter – common on windswept Orkney.

Standing slightly further along the coast on the Point of Nether Queena there’s a mysterious whalebone sculpture with downcurved ‘wings’ that looks like an owl in flight. It stands looking out to sea, surveying some of the roughest waters around the islands, where the Atlantic and North Sea meet. The whalebone is covered with yellow lichen and is rough to the touch. I was keen to investigate who put it there, when did they do it and why?

I had assumed it to be an art project from the 60s – on a visit to the Pier Arts Centre you’ll be confronted with similar sculptures. Maybe this was a modern Standing Stone! However, when I spoke to folk from Birsay like Albert Spence, Tommy Matches, Kenny Ross, Johnny Johnston and Bertie Harvey I discovered the whalebone was a lot older than I had thought!

In the 1870s a large whale was washed ashore in Doonagua Geo, the stony beach below where the bones stand. Albert Spence told me that his Grandmother recalled walking hand in hand with her twin sister – they were taken to the shore as young children in the 1870s to see ‘the big fish’! Going by her age we could narrow the date to approximately 1876.

The whale was a Baleen whale (that filter-feed on plankton) as there are holes in the jawbone (part of which makes the supporting post) for filters. Some have suggested that it was a sperm whale, but the lack of whale’s teeth in Birsay and the lack of tooth sockets in the jawbone suggest otherwise. A whale expert came to the conclusion that the bones were from a Right whale. Right whales (pictured below with calf) were named by whalers who considered them the “right” whales to hunt, since they were rich in blubber, easy to catch (they are relatively slow swimmers) and they floated after being killed. Right Whales could be up to 60ft long and it is assumed that the whale was already dead when it washed on the shore at Birsay.

These days a whale being washed ashore would be considered an ecological disaster, but at that time it was like a harvest to the folk of the Northside. The Northside area was more isolated then, the present road being constructed forty years later. Orkney communities tended to share whatever they had with each other in the old days, but they were also very territorial – fishing rights were fiercely guarded as this was their food supply. Southside men fished in their own, seperate, area.

At that time, a company from Leith bought beached whales and boiled down the blubber and ground down the whalebone to be used as bonemeal for fertiliser. However, the men of Northside decided that they could do this work themselves and make more money so they bought the whale carcass from the receiver of wrecks and assumed ownership of it.

However, this plan backfired. Though the men of Northside cut up the carcass and made use of every bit they could, oil, bones, and meat; they did not have the correct lifting equipment and couldn’t roll the whale over to get at the blubber on the side that lay on the shore. Whaling ships had 20 strong men in their crew and there were not enough men in Northside to physically do the job. Though the folk of Northside did not lose money – selling whale oil was very lucrative at the time – there was great disappointment surrounding the whale.

What happened next is unclear. The remains of the whale were left for some time. Kenny Ross’s grandfather (who was born in 1898) recalled being taken to see the remnants of the whale, so it must have remained on the beach for at least 25 years. One can only imagine the smell! There is some speculation that parts of the whale were washed away due to the fact there are not more whalebones around Birsay. However, evidence is unclear – as the whale decomposed, bones would have been easy to extract – and many bones would have been sent away to be ground up for fertiliser.

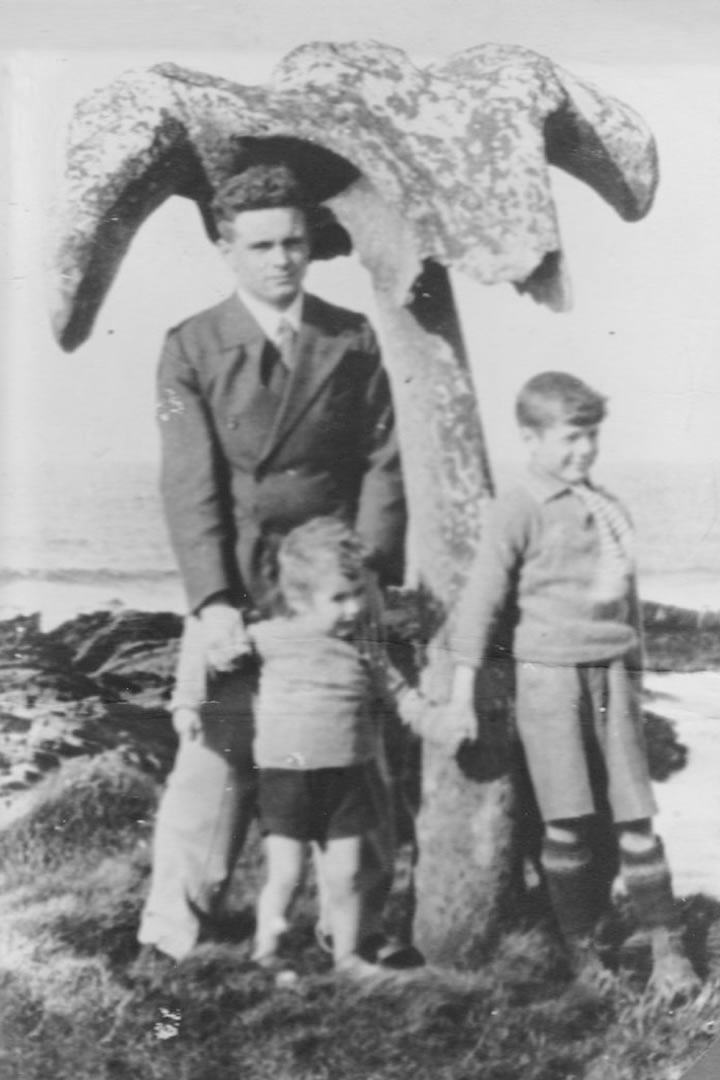

Given that it would have taken considerable time for the flesh to rot from the bones, we can only suppose that the whalebone sculpture was not erected until at least 1880 – four or five years after the whale was washed ashore. The families in the area were Spences, Mowats, Johnstons and Taylors but who erected the Whalebone sculpture is not recorded. The post is part of the jawbone. The top or crossbar of the whalebone sculpture is the back of the skull. The skull of a much smaller whale in Stromness shows similarities to the Birsay crossbar.

Albert Spence recalls that the opposite side of the jawbone lay on a sheet of iron used to cover a peat stack (and keep it dry) at the farm of Hayon. A piece of vertebra was used as a milking stool, while another piece was used by Kenny Ross’ Great Aunt to make a comfortable kitchen seat! The vertebra pictured below was found at the Glebe in Harray and gives an impression of what a massive beast this must have been.

At the Kirbuster Farm Museum (run by the Orkney Islands Council and free to visit!) there’s another whalebone arch – made from two ribs and a vertebra. It is rumoured that these bones came from the same whale as those of the Birsay Whalebone, but this was built in more recent times.

At Binscarth in Finstown there was once an unusual archway called Whale Bone gate, formed by the massive jaw bones from a different whale. This was pulled apart to allow wider trailers to pass through, but whalebones can still be found used as fenceposts in the hill opposite the farm. Using whalebones for practical or decorative purposes was a common practice in Orkney – but what purpose did the Northside Whalebone sculpture have?

The best suggestion I have heard was that the whalebone was possibly a fishing mark to obtain a cross bearing. Landmarks, such as Costa Head, were lined up with other coastal features to give an idea of where to fish and to mark a safe route in from the sea; and the whalebone would have been very visible! The rock cairn shown in middle of this older picture of Skiba Geo below had a similar purpose – it (along with another cairn) was used to direct sailors to shore safely through this narrow channel, avoiding skerries.

Other suggestions I have heard is that perhaps erecting the whalebone was superstitious – a mark of respect for the huge creature – a whale gravestone if you like. Another suggestion is that the whalebone is simply a landmark – a destination to walk to – for a walk without purpose is not so satisfactory! However, walking for recreation was uncommon on those days, and given that it recently took four men to lift the crossbar (which now weighs 140lbs but would have been 20lbs heavier before it eroded) onto the post, it seems unlikely that erecting the whalebone was a task undertaken without purpose!

The Birsay whalebone has now stood through 130 summers and harsh Orkney winters (the photo above was taken in the 1930s) – but it has not always come out unscathed. A photo from 1982 shows the crossbar slipped halfway down the jawbone. Over time it came loose, not helped by children swinging from it! It was fixed by the Birsay Heritage Trust in 1997 – a rod was put through the whalebone to tighten it up, and the skull piece was reattached higher up the post and held together by wood and cunningly concealed stainless steel bolts.

After a terrible storm on 25th January 2008 the jawbone post broke and the whalebone was blown down. There were fears that the whalebone could not be saved, but thanks to the work of Birsay Heritage Trust again, it was repaired. The jawbone is hollow, so this was strengthened by inserting a metal rod and attaching a concrete base.

On 22nd May 2008 the whalebone was resited and now stands proudly again, a couple of metres further back from the cliff edge, a must-see for any visitor to Orkney. Perhaps if no other purpose can be found we can be satisfied that the whalebone now provides a fine subject for photographers on one of the best coastal walks in Orkney!

Grateful thanks to Albert Spence, Johnny Johnston, Tommy Matches, Kenny Ross, Tom Muir, Bertie Harvey, Johnny Johnston and Orkney Islands Council for their help in writing this article!

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!